Dwight Eisenhower's Crusade in Europe

by Anders Skovly

Introduction

During the second world war, Dwight Eisenhower served as the top commander of all Allied forces during the Allied invasions of northwest Africa, Italy, and France. His story, presented in the 1948 book “Crusade in Europe: A Personal Account of World War II”, is honestly rather boring and not something I would recommend many people to read in full, but there are some intriguing details here and there. This article is a summary of the book.

The early war in the Pacific

On December 7th 1941, Japan launched its attack against the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Five days later Eisenhower was requested to see George Marshall (head of the US Army) at the War Department. The Phillipines, which at the time was a US territory, had also been attacked by the Japanese mere hours after the raid on Pearl Harbor, and Marshall wanted someone familiar with the Philippines to serve on his staff. That someone became Eisenhover, who had spent four years in the Phillipines in the late 1930's.

Both Marshall and Eisenhower believed that to fight back against Japan it was crucial to remain in control of the shipping lane between the United States and Australia. For this reason Eisenhower spent the next months arranging for garrison troops to be sent to various Pacific islands.

He also arranged for submarines and fast ships to make deliveries of critical items to the American-Philippino garrison at Bataan and Corregidor, where they were making their stand. This allowed the garrisons to hold out longer, but they could not last long enough for the US Pacific Fleet to come to their aid. With many ships destroyed or damaged at Pearl Harbor, the remainder of the Fleet was deployed defensively in early 1942. Thus, on April 9th the soldiers at Bataan ran out of supplies and surrendered. The surrender of Corregidor followed a month later.

Planning the liberation of Europe

Simultaneously as Marshall’s staff was working on the Philippine issue, they were also considering how to defeat Germany, who had declared war on the United States on December 11th. Landing an Allied invasion force somewhere in northwestern Europe made sense, as the landing site would be a relatively short distance from the industrial centers of Germany (the Ruhr and the Saar), and the terrain in that part of Europe was well-suited for offensive action, being much less mountainous than southern Europe. Additionally, all the forces defending Britain could be used offensively if the Allies were to strike just across the English Channel.

However, there were many who were concerned with the difficulties of attacking northwestern Europe. All along the coast of the continent the Germans were building fortified positions, referred to as “The Atlantic Wall”, and there were also many enemy air- and submarine bases in the region.

Many held that attack against this type of defense was madness, nothing but military suicide. Even among those who thought direct assault by land forces would eventually become necessary, the majority believed that definite signs of cracking German morale would have to appear before it would be practicable to attempt such an enterprise. A very few—initially a very, very few—took a contrary view.

Those few people believed that the solution could be found in the great potential of the American war industry, that is, in mass production of so many fighters, bombers, landing craft and warships as to completely overwhelm the defenders in the selected landing area.

Marshall supported the plan of a cross-channel assault and presented the arguments to President Roosevelt, who sent him on to Britain to discuss the plan with the British war leaders. An agreement was reached that an operation against northwest Europe was to be the Anglo-American coalition’s principal war effort. This was in April 1942. After Marshall returned from Britain he appointed Eisenhower as the commander of American forces in Europe, and in June Eisenhower travelled to London to assume his new duty.

Bombing Germany by day

When the US Air Force initially began conducting bombing missions in Europe they would fly during the day, which had the advantage of permitting greater bombing accuracy. As fighters at the time had a rather limited range they could not escort the American bombers all the way from England to Germany, so flying by day meant the bombers could easily be engaged by enemy fighters.

The British Air Force had practiced day bombing earlier in the war, and had suffered such high casualties that they had been forced to switch to night bombing. It was therefore natural that Winston Churchill and others were telling the Americans they would waste their aircraft flying such operations.

The American General Spaatz, however, thought his bombers could handle it, seeing as they carried more high-caliber machine guns for defense than did the British planes. Eisenhower also wanted the American bombers to fly daytime missions as he believed that precision bombing of small targets would be a key to a successful cross-channel invasion, and he wanted the crews to start building experience in this type of mission.

The Americans therefore began to fly during the day. At first this went great, as the German fighter pilots were indeed overwhelmed by the volume of defensive fire coming from the bombers. However, after some time the Germans were able to devise effective counter-tactics and inflict unsustainable bomber losses. Luckily for Eisenhower, rapid production of new long-range fighters meant that the daytime missions could soon continue with the protective escort of said fighters, and the pilots could continue to build experience in precision bombing.

Planning Torch

The Allies did not have the vehicles nor soldiers to undertake a large cross-channel offensive in 1942. Despite of this, Stalin was demanding that America and Britain launch a “second front” that year, to relieve pressure on the Soviet Army at the eastern front. President Roosevelt, worried that Stalin might enter into peace negotiations with Hitler and make an Allied victory that much harder, went along with Stalin's demand and ordered the US military “to launch some kind of offensive ground action in the European zone in 1942.” In July, the British war leaders met with George Marshall and Ernest King (head of the US Navy) to discuss the best course of action. Three options were under particular consideration:

The first was the direct reinforcement of the British armies in the Middle East via the Cape of Good Hope route, in an effort to destroy Rommel and his army and, by capturing Tripolitania, to gain secure control of the central Mediterranean. The second was to prepare amphibious forces to seize northwest Africa with the idea of undertaking later operations to the eastward to catch Rommel in a giant vise and eventually open the entire Mediterranean for use by the United Nations. The third was to undertake a limited operation on the northwest coast of France with a relatively small force but with objectives limited to the capture of an area that could be held against German attack and which would later form a bridgehead for use in the large-scale invasion agreed upon as the ultimate objective. The places indicated were the Cotentin Peninsula or the Brittany Peninsula.

Eisenhower, while acknowledging that the third option would be costly, told Marshall that he favored this option because any Mediterranean operation in 1942 would certainly delay the planned large-scale invasion of France from 1943 to 1944. Nonetheless, Marshall and King and their British counterparts decided upon an invasion of French northwest Africa. This operation was named “Torch”.

If the invasion was successful, it was thought that Allied shipping off the Atlantic coast of Africa would be safer due to the elimimation of suspected Axis air- and submarine bases in Vichy-French territory. (Eisenhower comments later that they never found any evidence of northwest Africa having been used as an Axis submarine base. He doesn't mention if there was any evidence that the region had been used by Axis air power.)

Further, if the Allied forces in northwest Africa advanced sufficiently far to the east (to Tunis and Bizerte), it would become possible to send relief convoys to Malta under the protection of Allied aircraft operating from Africa. And if the northwest invasion force together with the British force in Egypt should be able to clear all Axis units from Africa, then Allied ships could sail to the Middle East and Asia through the Mediterranean ocean and the Suez canal, rather than having to go all around Africa. (I think there were two primary benefits from this, one being easier aid to the Soviet Red Army through the ports in Persia (Iran), the other being easier supply of British troops fighting the Japanese in Burma.)

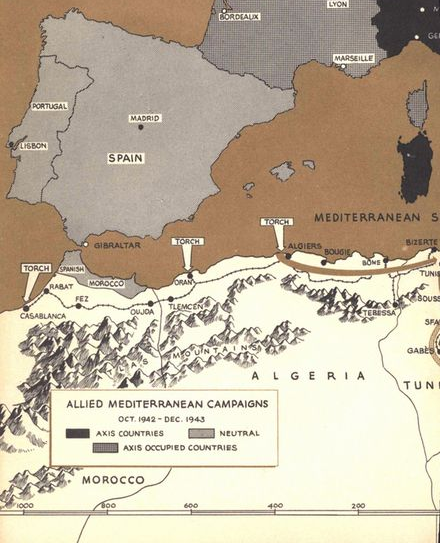

Any invasion site had to be within the range of fighters operating from Gibraltar, to prevent the possibility of German bombers destroying the convoys carrying the landing forces. Within this range there were four significant ports in northwest Africa: Casablanca, Oran, Algiers, and Bône (today called Annaba).

Due to the number of ships available, no more than three of these ports could be assaulted. Two of these were to be Oran and Algiers, as “both were important ports” (I assume this is supposed to mean that they were the best ports among the four available). Also, Oran was located near airfields that would improve Allied air power, while Algiers was the center of political, economic, and military activity in the area.”

The third port was to be either Casablanca or Bône. The appeal of Bône was its proximity to Tunis and Bizerte, which could enable a quick capture of those cities before the Axis could react to the Allied landings. The appeal of Casablanca was that it was an Atlanic port from which a railroad ran eastwards to the other ports. The Allied leaders worried that once they landed in Africa, the Spanish dictator Franco might allow German forces into Spain, in which case the Germans could use aircraft and artillery to close the strait of Gibraltar and prevent the Allies in Africa from being supplied through the Mediterranean ports. If this should happen, control over Casablanca would permit the troops to be supplied by railroad.

Eisenhower preferred choosing Bône as the third port, thinking that part of the force landing at Oran could move westward and take Casablanca by land. Marshall, however, deemed this too risky and decided that Casablanca had to be the third port.

Victory in Africa

In early November the Allied invasion convoys were sailing towards Africa, and Eisenhower travelled to Gibraltar where “our headquarters was established in the most dismal setting we occupied during the war. The subterranean passages under the Rock provided the sole available office space, and in them was located the signal equipment by which we expected to keep in touch with the commanders of the three assault forces. The eternal darkness of the tunnels was here and there partially pierced by feeble electric bulbs. Damp, cold air in block-long passages was heavy with a stagnation that did not noticeably respond to the clattering efforts of electric fans. Through the arched ceilings came a constant drip, drip, drip of surface water that faithfully but drearily ticked off the seconds of the interminable, almost unendurable, wait which occurs between completion of a military plan and the moment action begins [...] We had three days to wait. Finally the leading ships steamed in at night through the narrow strait and we stood on the dark headlands to watch them pass.”

The landings took place early on November 8th. In Algiers the French resistance was minimal and the city was quickly secured. On the following day the French General Henri Giraud, who had previously been smuggled out of France and was working for Eisenhower, flew to Algiers to try to end French resistance in the region. “He made a broadcast, announcing assumption of leadership of French North Africa and directing French forces to cease fighting against the Allies, but his speech had no effect whatsoever. General Giraud’s cold reception by the French in Africa was a terrific blow to our expectations. He was completely ignored.”

Coincidentally, the Commander of the French military, Francois Darlan, happened to be present in Algiers when the Allies took the city. As Darlan was a nazi collaborator he was not well regarded by the Allies, but when Giraud was unable to exert authority Eisenhower turned to Darlan.

On the 10th the two struck a deal in which Darlan was permitted to take administrative control over French North Africa. In exchange, Darlan ordered all French forces to cease fighting, which ended the fighting near Casablanca (Oran had been captured just before Darlan’s order was given). French forces in Tunisia were also expected to follow the order and allow the Allies to take Tunis and Bizerte, but German troops had began to enter those cities on the 9th and quickly assumed control over eastern Tunisia.

An additional benefit of the deal with Darlan was civil order. The population of northwest Africa wasn’t as eager to be liberated from "Vichy-Nazi domination" as had been anticipated, and Eisenhower believed that cooperation with Darlan was needed to prevent rebellion. “The Arab population was then sympathetic to the Vichy French regime, which had effectively eliminated Jewish rights in the region, and an Arab uprising against us, which the Germans were definitely trying to foment, would have been disastrous. Without a strong French government we would be forced to undertake military occupation. The cost in time and resources would be tremendous. In Morocco alone General Patton believed that it would require 60,000 Allied troops to keep the tribes pacified.”

Simultaneously as Eisenhower’s forces had landed in northwest Africa, the Axis troops in Egypt had been defeated in a battle at El Alamein. The Axis subsequently retreated west, first to Tripoli and then to eastern Tunisia, where they joined the troops already holding that territory. The British Eight Army followed in pursuit and, together with Eisenhower’s soldiers, cornered the Axis at the Tunisian coast.

Allied forces captured both Tunis and Bizerte on May 7th 1943, half a year after Eisenhower’s operation had begun, and all Axis resistance in Africa ceased five days later. As many as a quarter of a million enemy soldiers were taken prisoners.

Invading Sicily

Planning for the next Allied operation following victory in Africa had been initiated at the Casablanca conference in January 1943. My own opinion, given to the conference in January, was that Sicily was the proper objective if our primary purpose remained the clearing of the Mediterranean for use by Allied shipping. Sicily abuts both Africa and Italy so closely that it practically severs the Mediterranean, and its capture would greatly reduce the hazards of using that sea route. On the other hand, if the real purpose of the Allies was to invade Italy for major operations to defeat that country completely, then I thought our proper initial objectives were Sardinia and Corsica. Estimates of hostile strength indicated that these two islands could be taken by smaller forces than would be needed in the case of Sicily, and therefore the operation could be mounted at an earlier date. Moreover, since Sardinia and Corsica lie on the flank of the long Italian boot, the seizure of those islands would force a very much greater dispersion of enemy strength in Italy than would the mere occupation of Sicily, which lies just off the mountainous toe of the peninsula.

Both Eisenhower and Marshall continued to believe that a cross-channel assault into west Europe was the key to defeating Germany, and that this should not be put at risk of delay by any large operation in the Mediterranean. For this reason they were averse to attacks on Sardinia and Corsica, which would only represent the first step in an invasion of the Italian mainland. It was believed that if the Allies chose to take Sicily and ceased offensive action in the Mediterranean following its capture, the garrisoning of Sicily would not require a large amount of manpower and was therefore unlikely to delay the operation against France. For these reasons it was decided at Casablanca that Sicily was to be the next objective.

(I'm not that interested in going into further detail about Sicily. Suffice to say that the Allies landed on the island in July, that Mussolini was made to resign as Prime Minister later that month (to be replaced by Field Marshal Pietro Badoglio), and that all Axis forces had been withdrawn to the Italian mainland by the middle of August.)

Invading Italy

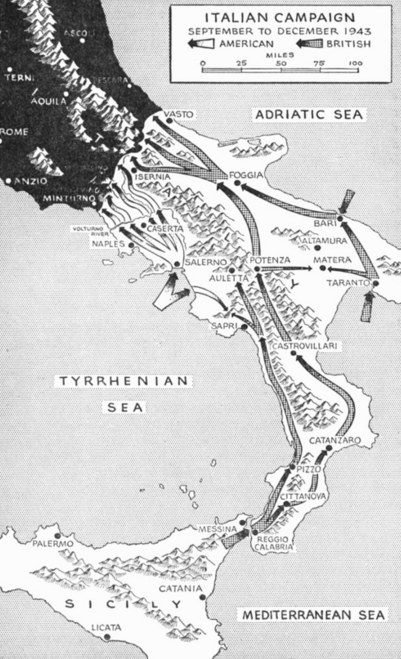

Following the capture of Sicily, Eisenhower decided that an operation against southern Italy could be conducted without interfering with the 1944 cross-channel plan. The main objective was the airfields at Foggia, which were suited for launching bombing missions against central Europe. Another goal was Naples, whose large port would be important in the supply of Allied forces in Italy. Eisenhower also hoped that landings on mainland Italy would make the Italian government capitulate. This would force the Germans to assume the occupation of the Balkans with their own soldiers, thus draining their manpower.

In fact, the Allies and the Italian government were engaged in secret talks about an Italian surrender. They reached an agreement that a surrender would be announced on September 8th shortly before the Allies landed at Salerno south of Naples. (Eisenhower doesn’t say anything about what happened to the Italians following the surrender. From what I've read elsewhere, German forces had entered Italy following Mussolini’s resignation as Prime Minister, and the Germans quickly took control of the country after the surrender was broadcast.)

Both Foggia and Naples fell to the Allies within a month after they stepped onto Italy. According to Eisenhower, the main objective of further fighting in Italy was merely to keep German forces away from France. (Thought I'm not sure those who continued to fight in Italy saw it that way...)

The air raid on Bari

On December 2nd 1943, German bombers struck against the port of Bari at the southern Adriatic coast of Italy, where they caused the destruction of sixteen Allied ships. Eisenhower writes that “one circumstance connected with the affair could have had the most unfortunate repercussions. One of the ships was loaded with a quantity of mustard gas, which we were always forced to carry with us because of uncertainty of German intentions in the use of this weapon. Fortunately the wind was offshore and the escaping gas caused no casualties.”

When I was reading the amazon.com customer reviews of “Crusade in Europe” I came across one reviewer claiming that “Eisenhower outright lies” in claiming that there were no casualties. Investigating this a little further I found extracts from a preliminary report on the Bari incident, “Toxic gas burns sustained in the Bari harbor catastrophe”, written by Doctor Stewart Alexander and dated 27th December 1943. A paragraph from the report reads: “More than 800 casualties were hospitalized following the raid. Of these casualties, 628 were suffering from mustard exposure. Sixty-nine deaths, wholly or partially caused by mustard, had occured as of 17 December.”

Half a year later a final report was released, stating that a total of 83 had died wholly or partially from mustard exposure at Bari. The reports and their contents were kept secret for many years. Extracts from both reports are available here: https://docslib.org/doc/2502692/the-bari-incident-chemical-weapons-and-world-war-ii

Further, according to “Toxic Exposures” by Susan Smith, “General Dwight D. Eisenhower accepted the evidence of the presence of mustard gas in the attack and approved Dr. Alexander’s report for release to the appropriate military authorities.“ (Source: https://dokumen.pub/toxic-exposures-mustard-gas-and-the-health-consequences-of-world-war-ii-in-the-united-states-9780813586120.html)

So it appears that Eisenhower was indeed not telling the truth when he wrote that the “gas caused no casualties”. It is of course understandable that he cannot violate military secrecy regarding the details of the event. Still, I don’t understand why he makes the claim that there were zero casualties caused by the mustard. There was no need for him to even mention the incident if he couldn't write the truth about it. This one falsehood makes the rest of “Crusade in Europe” less reliable as source material. After all, we can count on him pulling a similar move elsewhere in the text.

Planning Overlord

In December 1943 President Roosevelt told Eisenhower that he would command the operation in northwest Europe, which had then been named “Overlord”. In early 1944 Eisenhower relocated to London, where the Overlord plan was already well underway. One important aspect of the plan was when to launch the invasion. Due to the weather in the English Channel, the month of May was the earliest time the operation could be launched.

Eisenhower thought the operation should ideally start as soon as possible, since the Germans were continously improving their coastal defenses, and their rocket weapons (the V1 and V2) were being made ready to strike England from the coasts of France and Belgium.

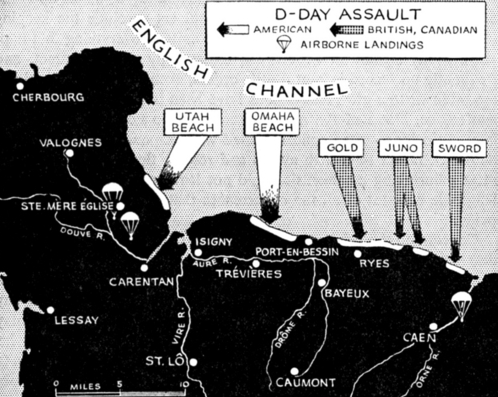

Despite of this, the target date was set to June. This was mainly due to Eisenhower’s decision that the initial invasion force should be expanded from the previously planned three divisions up to five divisions (plus three airborne divisions). Such an expansion required additional landing craft, which could not be ready in May.

Additionally, a key part of the plan was to use bombers to damage critical points along roads and railroads running into the invasion area, in order to hamper the enemy’s ability to reinforce their defenses. As the weather early in the year was expected to make precision bombing difficult, whereas the weather in May was expected to be more cooperative, delaying the invasion to June gave the bombers a better chance to succeed in their part of the operation.

There were several factors that limited the exact date Overlord could begin. The Allied planners wanted the invasion fleet to embark from England under the cover of night, so that its strength and direction would be unknown to the Germans for as long as possible. They wanted the troops to land approximately fourty minutes after sunrise, as this would give the bombers and warships time to complete their precision strikes against German positions on the landing beaches before the Allied ground troops arrived. The time of the landings had to coincide with a low tide, because this would render most of the German beach obstacles ineffective.

(Erwin Rommel, the German Field Marshal who was in charge of the beach defenses, assumed that the Allies would land at high tide and gave priority to construction of high-tide obstacles. These would not be submerged at low tide and would therefore not obstruct the landing crafts during a low-tide landing. The downside to the Allies of choosing a low-tide landing was that the waterline at the beach would be much further away from the German positions, meaning that the troops would have to advance further and be exposed to more enemy fire before being able to overrun the German positions. The Overlord planners believed that the beach obstacles posed the greater threat and therefore opted for a low-tide landing. Different types of beach obstacles are described at https://www.junobeach.org/beach-obstacles/)

In addition to needing a low tide about fourty minutes after sunrise, the Overlord planners also wanted the invasion night to have a decently bright moon, so that the airborne troops dropped during the night could navigate to their target positions. All these factors made June 5th, 6th and 7th the first dates Overlord could be launched.

Eisenhower believed that the early capture of Cherbourg, a port to the northwest of the landing area, was important for ensuring the success of Overlord. The landing area which could make early capture of Cherbourg most feasible was a beach the Americans called Utah. This beach was separated from the inland by a lagoon with only a few causeways running through. Eisenhower worried that if the Germans quickly seized the causeway exits, the soldiers landed at Utah would essentially be trapped and could be eliminated by German artillery strikes. To prevent such entrapment, two airborne divisions were to drop inland during the night to take control of the exits.

Another location Eisenhower wanted to capture early was the open plains south of Caen, where airfields could quickly be established. There, the large number of Allied fighter-bombers could have bases close to the front lines, which would enable more efficient air support of the ground forces. Caen was expected to be well defended, but Eisenhower hoped that speed and surprise would enable the Allied troops to occupy the plains early on.

The liberation of France

On June 4th, Eisenhower received a forecast for the next day’s weather at the Normandy coast. “Low clouds, high winds, and formidable wave action were predicted to make landing a most hazardous affair. The meteorologists said that air support would be impossible, naval gunfire would be inefficient, and even the handling of small boats would be rendered difficult. Admiral Ramsay thought that the mechanics of landing could be handled, but agreed with the estimate of the difficulty in adjusting gunfire. General Montgomery, properly concerned with the great disadvantages of delay, believed that we should go.” All things considered, Eisenhower thought it best to postpone the invasion from the 5th to the 6th.

Early on the 5th he received yet another weather report. The weather at the Normandy coast was as harsh as had been predicted. The forecast for June 6th was much more promising, although bad weather was expected to resume again after a day or two.

This meant that if the first part of the invasion force hit Normandy on the 6th, it may become impossible to reinforce them in the following days due to the weather, which would put the men then in Normandy in a vulnerable position against a German counter-attack. There was therefore a siginificant risk to launching the operation on the 6th, but Eisenhower judged that they would have to chance it, as it was also risky to postpone and give the enemy yet more time to prepare their defenses. He announced to his assembled commanders that they were going ahead the next day.

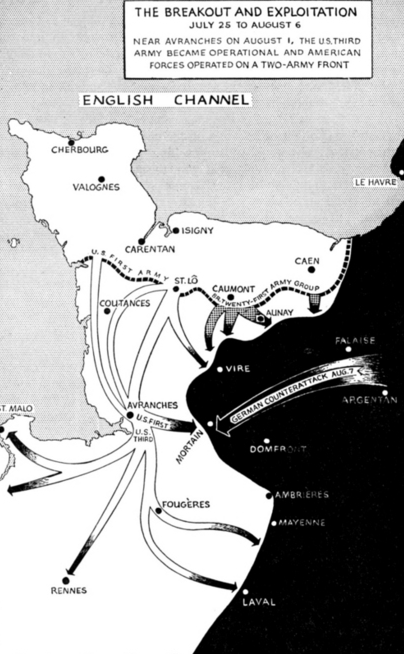

Eisenhower doesn't give much detail about what actually happened on the "D-Day". After the Allies were ashore in France, the port of Cherbourg was captured after twenty days, whereas Caen and its plains proved a more difficult task. Apart from Cherbourg, the frontline in Normandy was fairly static for the first month and a half, during which time the Allies were building up strength for a decisive offensive. That offensive began on July 25th along the western part of the frontline, where American troops attacked south towards Avranches and thereafter spread out to the west, south and east.

As the enemy saw the American First Army attack gather momentum to the southward and finally break through the Avranches bottleneck, his reaction was swift and characteristic. He immediately moved westward all available armor and reserves from the Caen area to counterattack against the narrow strip through which American forces were pouring deep into his rear. His attack, if successful, would cut in behind our breakout troops and place them in a serious position. Because our corridor of advance was still constricted the German obviously felt that the risks he was assuming were justified even though, in case of his own failure, the destruction he would suffer would be vastly increased. His attacks, which were thrown in at the town of Mortain, just east of Avranches, began on August 7.

The Americans had enough strength to both hold the German counterattack at Mortain and simultaneously move forces southeast around the Germans to create an encirclement, later known as “The battle of the Falaise pocket”, in which a significant defeat was inflicted upon the Germans. In the weeks following the Falaise battle the remaining German forces were rapidly pushed eastwards towards Germany, and the large and important Belgian port of Antwerp fell into Allied hands in early September.

The Ardennes offensive and German surrender

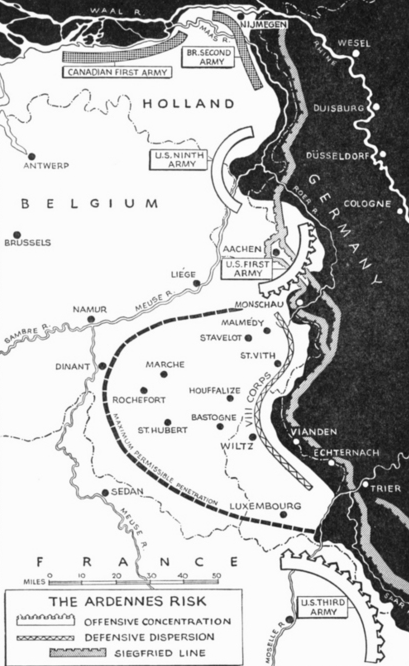

In December, the Germans had retreated back to Germany and were holding a defensive line along the Westwall, a line of fortifications built in the late 1930’s. The Allies were prioritizing their strength on two offensive sectors: one just north of the Ardennes region, and one just south of it. This prioritization came at the cost of reduced defensive strength in the Ardennes, but Eisenhower believed the potential gain from continuing the two offensives outweighted the risk of a breach in the Ardennes, as it seemed unlikely that the enemy would be in a position to mount a large-scale attack after having lost a significant share of their manpower in France so recently.

General Bradley estimated that if the enemy should deliver a surprise attack in the Ardennes he would have great difficulty in supply if he tried to advance as far as the line of the Meuse. Unless the enemy could overrun our large supply dumps he would soon find himself in trouble, particularly in any period when our air forces could operate efficiently. In the area which Bradley believed the enemy might overrun by surprise attack he placed very few supply installations. We had large depots at Liége and Verdun but he was confident that neither of these could be reached by the enemy.

On December 16th, the Germans did in fact launch a surprise offensive through the weak Allied line and into the Ardennes, their main objective being to reach Antwerp to deny that port from the Allies and to sever the land connection between the Allied forces in the North from those in the South. As Bradley had predicted, the Germans never got too far through the Ardennes. By early January they were subject to Allied counter-attacks on both their northern and southern flanks and were retreating.

(In his book "The Rise and Fall of The Third Reich", William R. Shirer writes that "When a German armored group reached Stavelot on the night of December 17, it was only eight miles from the U.S. First Army headquarters at Spa, which was being hurriedly evacuated. More important, it was only a mile from a huge American supply dump containing three million gallons of gasoline." 1 American gallon is roughly 3.8 liters. I don't know if Eisenhower would consider a depot of over eleven million liters of fuel as "very few supply installations", but Shirer doesn't give any source for his claim, so I have some doubt about its accuracy.)

In the spring of 1945 the Allies crossed the Rhine at two locations north and south of the industrial Ruhr area and surrounded the hundreds of thousands of German soldiers defending the area. From the Ruhr they moved further east with ease as Germany’s western Armies were no longer able to mount significant resistance. The official German surrender followed not long after.