Bram Vanderstok's Escape from Stalag Luft III

by Anders Skovly

Introduction

During world war 2, many Allied airmen were shot down over German-occupied Europe. Upon capture they were sent to a prisoner-of-war camp administered by the German air force (Luftwaffe). Stalag Luft III was one such camp.

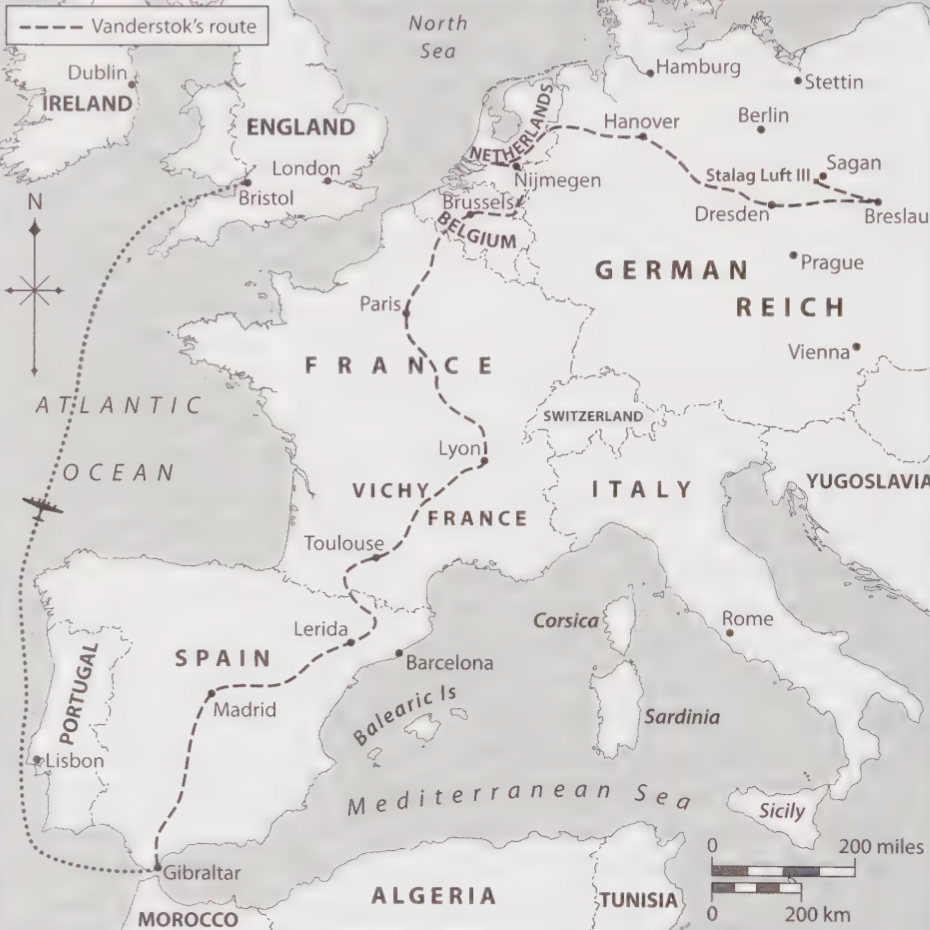

Bram Vanderstok’s war memoir “Escape from Stalag Luft III”, written some fourty years after the war, describes this Dutch pilot’s experiences from the brief struggle between Holland and Germany in 1940, his escape from German-occupied Holland to Britain to join the British royal air force (RAF), the air war between the RAF and the Luftwaffe over western Europe, his capture on the ground in Belgium after being forced to bail out of his aircraft, his imprisonment at and eventual escape from Stalag Luft III, and his journey through German-occupied Europe to Gibraltar, from where he was transported back to Britain to continue flying missions against Germany.

Far from escaping the Stalag on his own, Vanderstok was one of 79 prisoners who got out through an underground tunnel well over a hundred meters long. Using Vanderstok's war memoir as a basis, I here retell the story of their escape. (While Vanderstok also details how he ended up in the Stalag and how he got out of Germany proper, these parts of the story will not be covered here.)

Project Wooden Horse

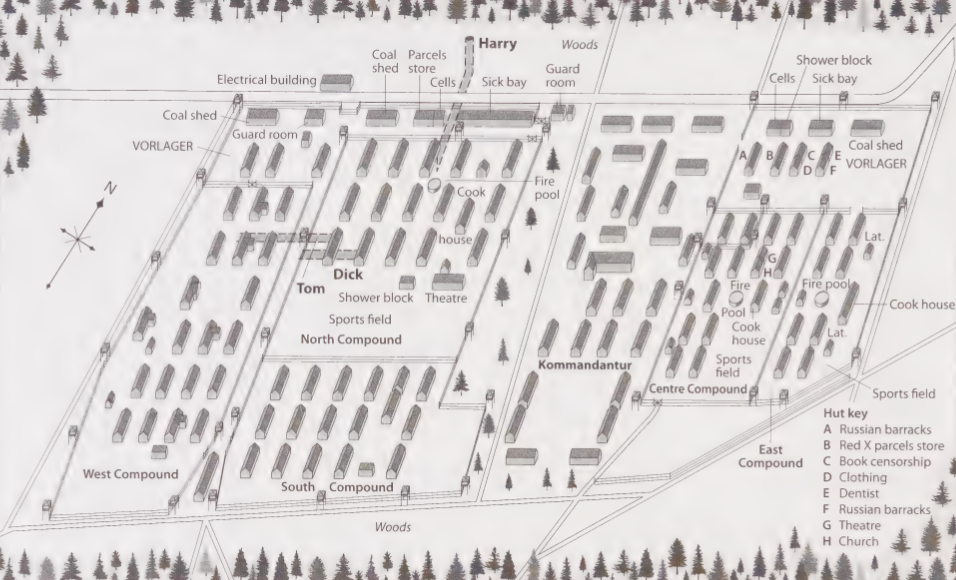

When Vanderstok arrived at Stalag Luft III in 1942 he was bent on escaping as soon as possible. From other prisoners, or Kriegies as he refers to them (kriegsgefangen, prisoner of war), he learned that there had already been many escape attempts: over thirty tunnels had been dug in the camp thus far, and all of them had failed, either due to tunnel collapse or discovery by the guards.

Yet another tunnel, dubbed “Project Wooden Horse”, was initiated after Vanderstok’s arrival at the Stalag. The camp contained a sportsfield, and to practice gymnastics the inmates had been permitted to construct a horse with a springboard and a padded top. During nighttime this horse was stored in the kitchen building. Every morning after the roll-call two prisoners would enter the hollow horse from the underside and sit on two seats mounted inside the horse. Other prisoners would carry the horse to the sportsfield, always putting it down in the exact same location. During the day the prisoners would perform gymnastics and other sports while the two men inside the horse dug away, filling bags of soil that were hung on hooks inside the horse. Before the horse was moved back to the kitchen the tunnel entrance was concealed below a trap door covered with soil.

After four months of digging, the tunnel had reached beyond the outer fence, and the prisoner’s “escape committee” decided that three men would attempt an escape. During the day they would enter the tunnel from inside the gymnastics horse, and when the horse was carried back to the kitched later in the day they would stay down in the tunnel and wait for nightfall. In the dark the three men would emerge outside the fence and cross the hundred-feet wide open area that separated the fence from the forest.

(The three men in the tunnel could not have covered the tunnel’s trap door entrance while they were down in the tunnel, so I’m not sure exactly how this was done without notice of the guards. Perhaps there were moments when the guards were unattentive or not around and the horse could be lifted to let someone crawl under to conceal the door.)

The plan failed due to the restricted air supply in the tunnel. The three men created an air hole in the tunnel’s exit shaft, which caused the shaft to partially collapse. This was noticed by a guard, and the three men were taken to the camp’s prison block.

Forged documents

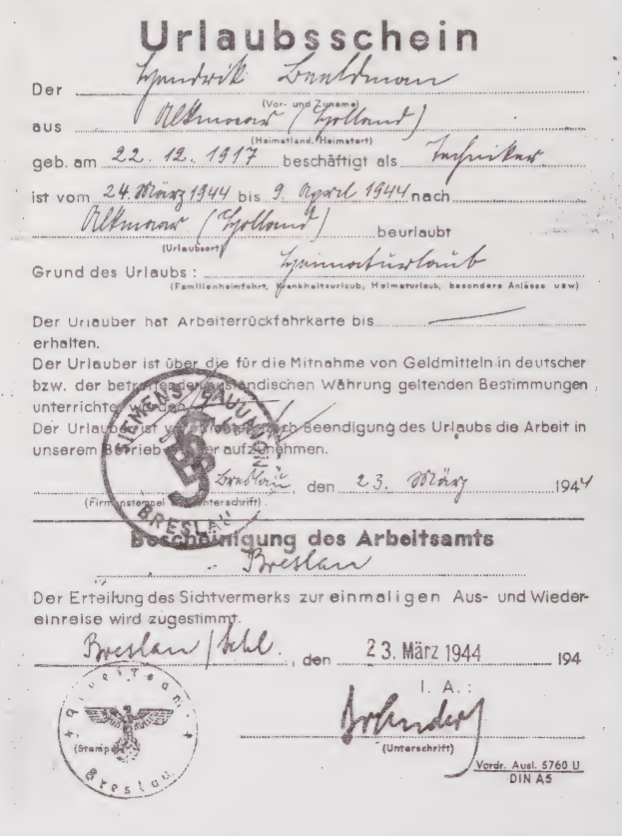

To not only escape from the camp itself but from all of German-occupied territory it was necessary to obtain a variety of items to aid the escapees once outside the fence. This included civilian-looking clothing, false documents, and German money. Vanderstok obtained a watercolor paint set and began practicing the forging of documents using a precision paintbrush with only a few short hairs.

Having been a student of medicine before the war, he was also able to get a part-time job in the camp’s hospital, from which he stole tape and glycerine and other stuff that might come in handy. Some of the prisoners were chemists by occupation, and with a chemist's aid the document forgers created ink by mixing soot, glycerine, ether and mineral oil. The ink was waterproof and made their forged documents usable even if they got wet.

Later on, the camp’s document forgers were joined by a goldsmith who was able to manifacture stamps. The prisoners would regularly receive red cross packages containing various items, including shoe rubber heels intended for shoe repairs. The goldsmith got one of the forgers to draw the mirrored outline of a stamp onto a piece of shoe rubber. The goldsmith then used a razor blade mounted on a handle to carve the rubber into a stamp.

Trade and theft

Apart from shoe rubber heels, the red cross packages also contained many luxury items such as chocolate, coffee, good cigarettes, soap, certain medications, and butter, all of which the German guards had restricted or no access to. These items made it possible for the prisoners to trade with guards to obtain useful items.

Unsurprisingly, not all the guards were involved in such trades. The ferret “Rubberneck” was never included in bribes or any other favours because we simply could not trust him. Apparently the ferrets received bonuses for finding escape materials and Rubberneck was, no doubt, their best man. He had found a few minor items: a screwdriver, a half-finished wire-cutter, and a stolen flashlight. He became arrogant and tried to make life unpleasant by searching rooms just when a meal was served, or by kicking over a basin of fermenting raisins. On several occasions he had hit prisoners with the butt of his Luger if they didn't move out of the room fast enough. He became one of the few real enemies, while many other guards were strict but not truly hateful.

At least a few guards became victims of theft. On one occasion a group of prisoners staged a musical concert. Guards were invited to front-row seats, and under the cover of dim light and music a number of them lost their wallets, courtesy of the prisoners seated in the second row. One guard detached his holstered pistol, which was snatched as the guards rose to give an applause at the end of the show.

Apart from money, one of the wallets contained a travel permit and a sheet of food stamps. The day after the concert the German owner of the pistol, Hauptmann Wiegel, came to Vanderstok to ask for help in retrieving the stolen gun. Wiegel didn’t have much of a choice but to ask, since reporting the theft of his gun to the camp leadership would probably get him into trouble.

Vanderstok conferred with the leader of the prisoner’s escape committee, and it was decided that the pistol would be given back to Wiegel in exchange for one hour’s access to Wiegel’s prison gate pass. When Vanderstok proposed the deal Wiegel reluctantly accepted, and one of the camp’s document forgers spent the next hour making a thorough copy of the pass.

At regular times, a group of prisoners was led out of the camp to perform some kind of work on the outside. The prisoner's escape committee decided that Vanderstok (who could speak German) was to put on a fake guard uniform, show the fake pass to the gate guard and walk out of camp with a group of other prisoners.

It almost worked. Down the road the group encountered Feldwebel Schwartzmann, the real guard who was supposed to lead the group of prisoners. Schwartzmann had arrived an hour earlier than expected, and when he realized what was happening he drew his gun and the whole group of escapees was marched off to the prison block.

Tom, Dick and Harry

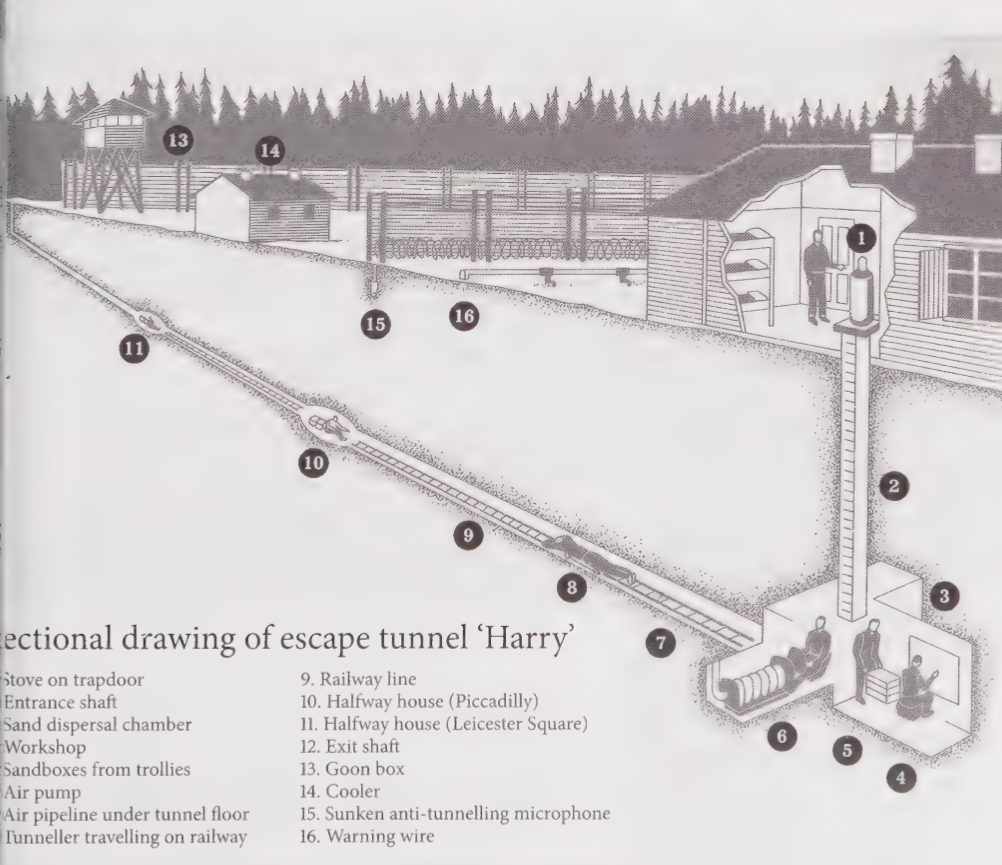

The escape committee's most ambitious project was that of “Tom, Dick and Harry”: the simultaneous digging of three tunnels intended to facilitate a mass escape. Each of the tunnels were to start from inside one of three barracks. Every barrack was lifted off the ground, with certain parts of the buildings being supported by large concrete boxes filled with soil.

In the case of the tunnel called Harry the entrance was hidden under a bedroom stove. The stove stood atop a platform of bricks, which the Kriegies chiselled free from the rest of the floor to gain access to the soil-filled concrete box and the ground below. Whenever someone was going into or out of the tunnel, the stove and brick platform had to be moved out of the way.

When Vanderstok was released from the prison block back into the camp these tunnels were already well underway. Aside from the forging of documents he contributed to the project by removing excavated sand. For this job the Kriegies used pairs of bags connected together by a strap to be worn over the neck. One bag of soil would hang down into each pant leg. When the prisoners wore coats the bags could not be seen by the guards.

The bags were tied shut with a knot at the bottom side. At an opportune moment the knots would be pulled open to slowly release soil onto the ground. A partner-prisoner would follow a little behind and walk in such a way as to mix the new soil into the ground. This method worked well, thought it was a bit slow even when many men were contributing. An alternative method was therefore devised.

We were instructed to save our Red Cross food parcel boxes, and at a roll-call more than a thousand Kriegies stood in line with a cardboard box under one arm. Hauptmann Pieber became nervous and more guards were called in for the daily counting procedure. Six ferrets walked between the long rows of prisoners and ordered us to open the boxes. The boxes were empty, and after the first hundred or so, Pieber stopped the inspection and asked Wings Day, “What is this about? Why are you carrying empty boxes?” Wings smiled and said, “Nothing to worry about. Just English humour.” Hauptmann Pieber looked at him and said, while shaking his head, “Well, you have had your English Humour. Now you'll take your boxes to the garbage bins and get rid of them!”

English humour was a sensitive point because it was always compared to German humour. The “psychologists” had made it well-known that we regarded German humour as being on the level of gross, dirty jokes, far below the level of the sophisticated and more civilized English jokes. Some of the ferrets and other guards laughed at the joke of the empty boxes. It all helped to confuse the German mind.

The next day, during the afternoon roll-call, we again appeared with boxes under our arms. Pieber tried to smile at the joke, saying, “OK, that’s enough of that. It was very funny, but no more! Anybody with a box tomorrow will get disciplinary punishment.” Then he dismissed the roll call. We lingered a little until the Germans marched off. Then we opened our boxes, which now were filled with sand from our tunnels, and emptied them onto the sports field. Four thousand feet shuffled the sand into the soil. We had got rid of the sand of ten days digging!

(Vanderstok writes that “Security did a remarkable job of regulating the traffic of sand-carrying stooges to places unobserved by Germans. The boxes, bags, or sacks never seemed to come from the buildings which actually housed the tunnel entrances. Even when a guard in one of the towers spotted a suspicious box or bag with his binoculars, the carrier came from the wrong hut.” This makes it seem like being caught with soil was not at all a big deal, and that the only concerns were preventing the Germans from realizing where it came from and to what extent the prisoners were digging. As noted in the beginning of this article, the prisoners had tried to dig a large number of tunnels and it had always ended in failure, so I assume the guards didn’t feel any need to force information out of the prisoners, or perhaps they didn’t do this out of adherence to the Geneva conventions. Still, if the trick with the boxes had failed and the guards found over a thousand prisoners carrying a box of soil, then the scope of the prisoner’s tunnel projects would have been revealed and camp security could have increased significantly. I think this seems like a risky gamble, considering they only sped up the soil-removal work by ten days, which doesn’t seem long compared to how long it took to complete the tunnel. (That time is not given in the book, but I get the feeling that it was roughly a year in the making.))

One day, the tunnel “Dick” was discovered when a guard came into the barrack for an inspection and happened to step onto the loose piece of concrete that covered Dick’s entrance. At this point the tunnel “Harry” was the longest one with more than 400 feet, not more than a few dozen feet away from reaching the forest, and the escape committee decided to focus all further effort on Harry. Keeping the guards at ease was now thought to be more important than before, so the tunnel “Tom” was relegated to a dumping ground for soil from Harry, in order to better hide the prisoner’s continued digging activity.

The escape

On March 19th 1944 the tunnel engineers believed they had reached the forest, and the escape committee decided that the escape would take place after the evening roll-call on the 24th. Two hundred prisoners were going to partake. The 24th arrived, and Vanderstok and the others got a proper scare when the guards decided to do a thorough search of the building containing Harry’s entrance. Luckily, the entrance was so well-hidden that the search party only found and confiscated a gasoline burner.

In the evening, a few men went down into the tunnel to dig the last two-three feet up to the surface. Upon completing the tunnel they found that they were not in the forest after all, they had emerged in the open area that separated the fence from the forest. This complicated matters a bit. The solution became to tie one end of a rope to the ladder in the tunnel's exit shaft, and to have the first man out of the tunnel bring the other end of the rope into the forest. From the cover of the trees he could then pull the rope when the coast was clear, to signal the next man to come out.

Vanderstok was the eighteenth man to pass through the tunnel. Quickly, I climbed up to the surface and immediately found the rope, which was attached to the top rung of the ladder. I felt no signal, so it was not safe yet. Then I felt the three distinct tugs and slowly popped my head up and looked in the direction of the camp. There I saw the barbed wire fence brightly lit by the lights along the periphery. The nearest Goonbox [watch tower] was at least two hundred feet away; but, indeed, I was twenty feet from the edge of the woods.

He climbs out and follows the rope into the forest, where he whispers “good luck” to the signalman before heading towards Sagan railway station. Vanderstok’s escape journey takes him through Holland, Belgium, France and Spain to Gibraltar, where he is transported to Britain to resume as a pilot in the RAF.

Of the two hundred prisoners planned to escape that night, 79 makes it through the tunnel before they are discovered. Only Vanderstok and two Norwegians, Jens Muller and Per Bergsland, manage to reach Allied territory. The other 76 men are captured, and fifty of them are executed on Hitler’s order.

Escaping in a hot air balloon?

In his story from life in the camp, Vanderstok mentions a group of four Americans who had gotten their hands on gasoline and a gasoline burner. He writes that they had planned to construct a hot air balloon to be made of bed sheets. The sheets were to be made airtight by soaking them in gasoline-dissolved shoe rubber from the red cross packages. Supposedly the Americans had given up on the project due to the difficulty of hiding all the materials.

To me, it sounds like the Americans might have had a wild fantasy of flying away in a balloon, but surely they could never have considered it seriously: even if they did manage to build the thing they would still have to take off from a location surrounded by guards with machine guns. But I do find the idea very curious: does soaking a bed sheet in gasoline-dissolved rubber actually make it airtight? And would it actually be possible to make a functional hot air balloon out of such sheets? It would have been fun to see someone like the Mythbusters put it to the test.