Translation in bacteria

With a focus on E. coli

© Anders Skovly 2025

This article explains how the base sequences of RNA are translated to the amino acid sequences of proteins.

mRNA, tRNA, and ribosomes

In the article "proteins and nucleic acids" it was said that "A gene is a base sequence in DNA that can be translated to the amino acid sequence of a protein. The translation of a gene to a protein is indirect: first the base sequence of DNA is transcribed ("copied") to RNA, and then the base sequence of RNA is translated to the amino acid sequence of a protein."

This was an oversimplification, as there also exist genes that are transcribed to RNA, but are not translated to an amino acid sequence. Genes that are translated to proteins are called protein-coding genes, while genes that are not translated to protein are called RNA-coding genes. The RNAs that are translated to amino acid sequences are called messenger-RNAs (mRNAs), while RNAs that aren't translated have different names depending on their function in the cell. Two examples are ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer-RNA (tRNA), both of which are important components of the translation process.

A ribosome is a large molecular structure composed of multiple different proteins and ribosomal RNAs held together by non-covalent interactions. A ribosome's role in translation is similar to that of RNA polymerase's role in transcription: A ribosome binds to an mRNA, facilitates the binding of two "complementary" amino acids to the mRNA, and catalyzes the formation of a covalent bond between the amino acids. Next, the ribosome moves along the mRNA while complementary amino acids continue to bind the mRNA, and covalent bonds are created between the amino acids so as to bind them together into an amino acid chain (a protein).

The amino acids don't bind directly to the mRNA. Instead, each amino acid binds to a tRNA, and the tRNA then bind to the mRNA. The binding between amino acids and mRNA is therefore indirect.

This figure shows the structure of a tRNA (the figure shows a tRNA from yeast, the tRNAs of bacteria are generally similar). A tRNA has four intra-molecular base paired regions (four sets of complementary sequences within the tRNA that base pair together). Such regions are often referred to as "stems". At the end of three of the stems is a "loop", while the fourth stem ends in the tRNA's 3'- and 5'-ends.

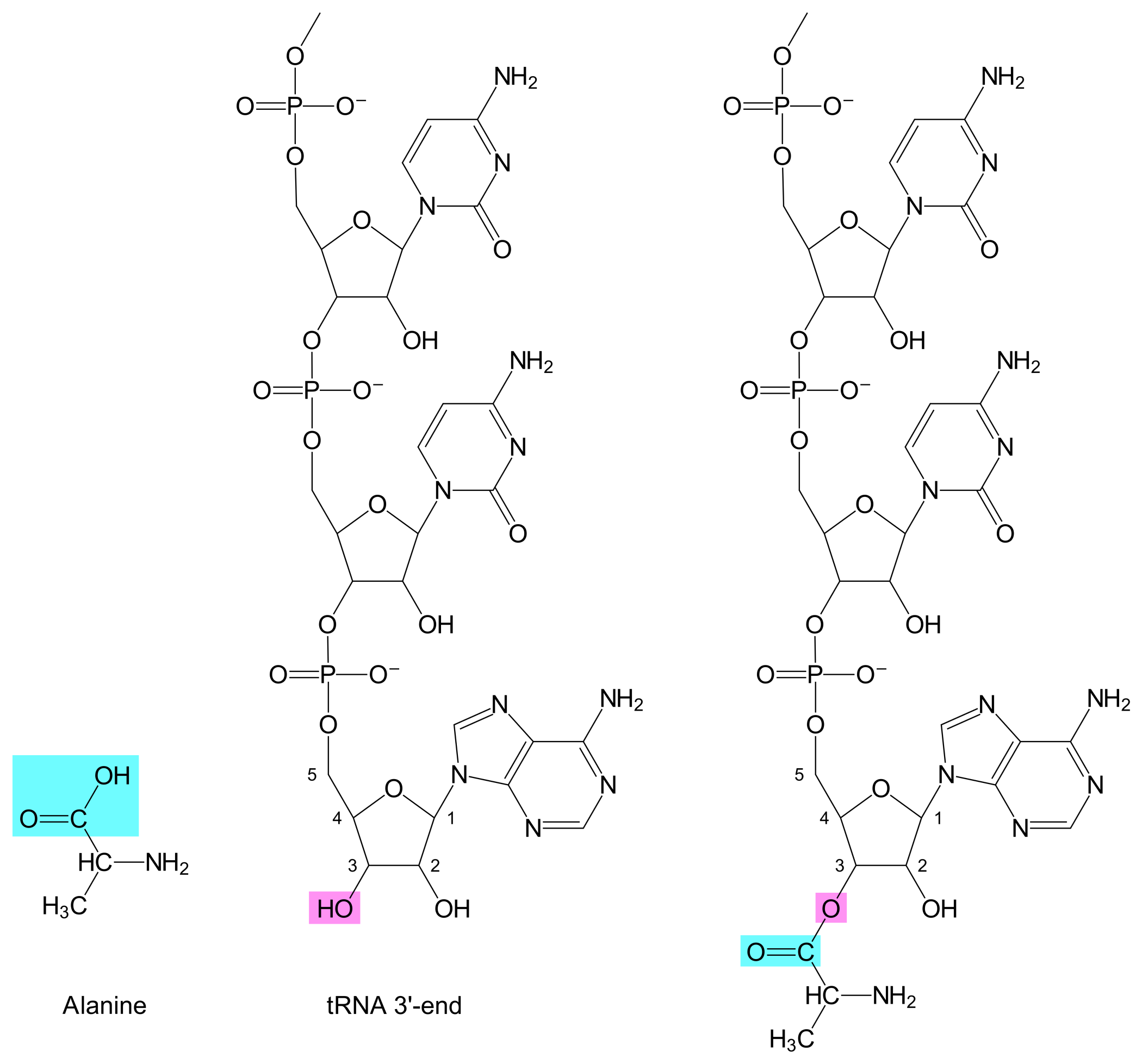

The stems and loops fold in such a way as to give the tRNA as 3D-structure that resembles an L. The tRNA's 3'-end is positioned at one end of the L. An amino acid can bind to the tRNA by means of a covalent bond between the amino acid's carboxylic acid group and the tRNA's 3'-hydroxyl group.

A tRNA can bind to an mRNA through base pairing between a base triplet in the mRNA and a base triplet in the tRNA. The base triplet in mRNA is called a codon, while the base triplet in the tRNA is called an anticodon. The anticodon is located in one of the three tRNA-loops, and is positioned on the opposite end of the L in comparison to the 3'-hydroxyl (see the figure linked above).

Translation of lacZ

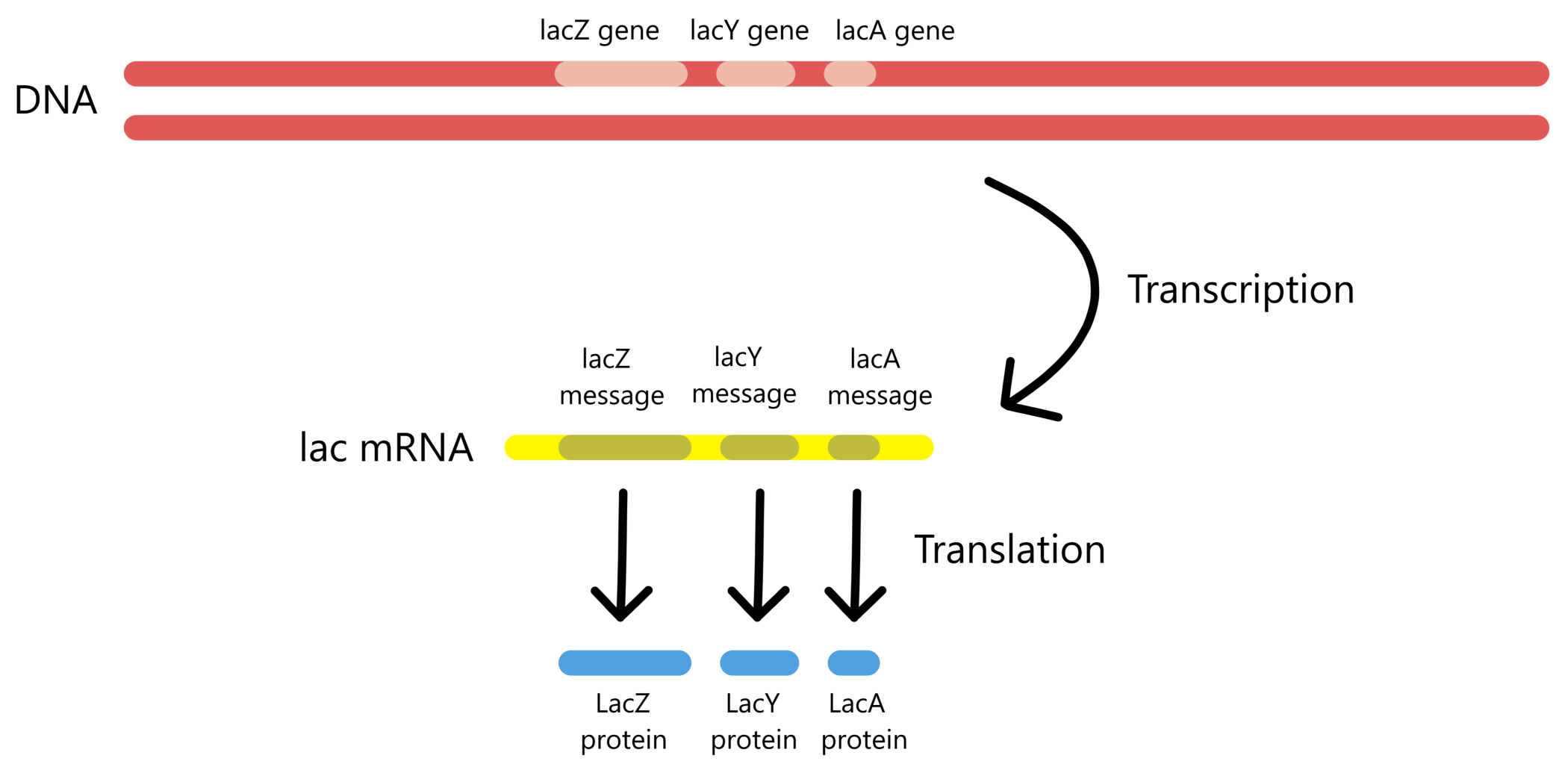

Translation will now be described with a practical example: the translation of the lacZ message in mRNA to a LacZ protein. As mentioned in the article about the lactose promoter, the three genes lacZ, lacY and lacA are transcribed to three protein-messages in one and the same mRNA. However, the three messages are translated individually. The sequence of the lacZ message is presented here in the form of the nontemplate sequence of the lacZ gene, displayed with red text.

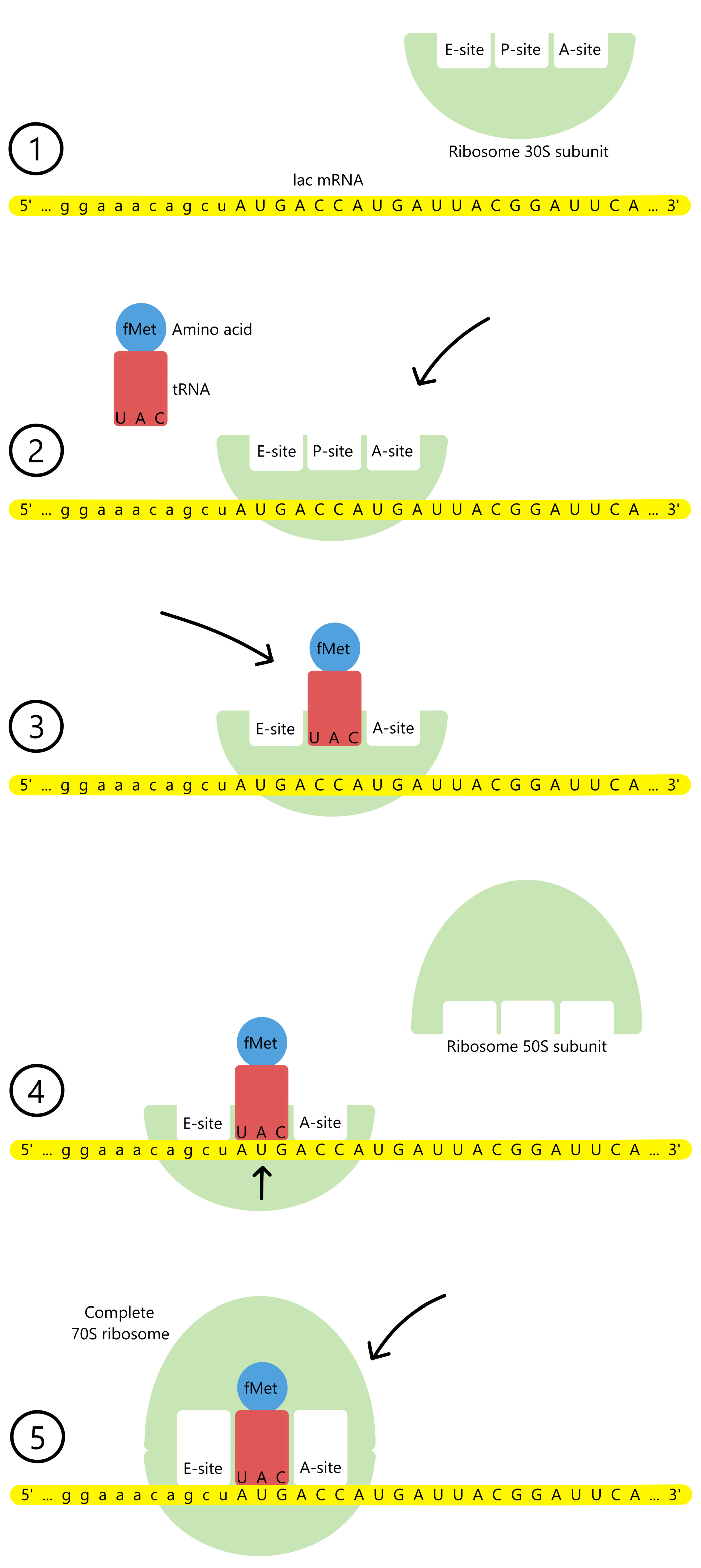

Before the translation of the lacZ message begins, the ribosome will exist in the form of two separate parts: a small ribosomal subunit (30S subunit) and a large ribosomal subunit (50S subunit). (The small subunit has a sedimentation coefficient of 30 Svedberg-units, and the large subunit has a sedimentation coefficient of 50 Svedberg-units, thus the designations 30S and 50S. Sedimentation coefficients don't have anything to do with translation, so it isn't necessary to understand them here.)

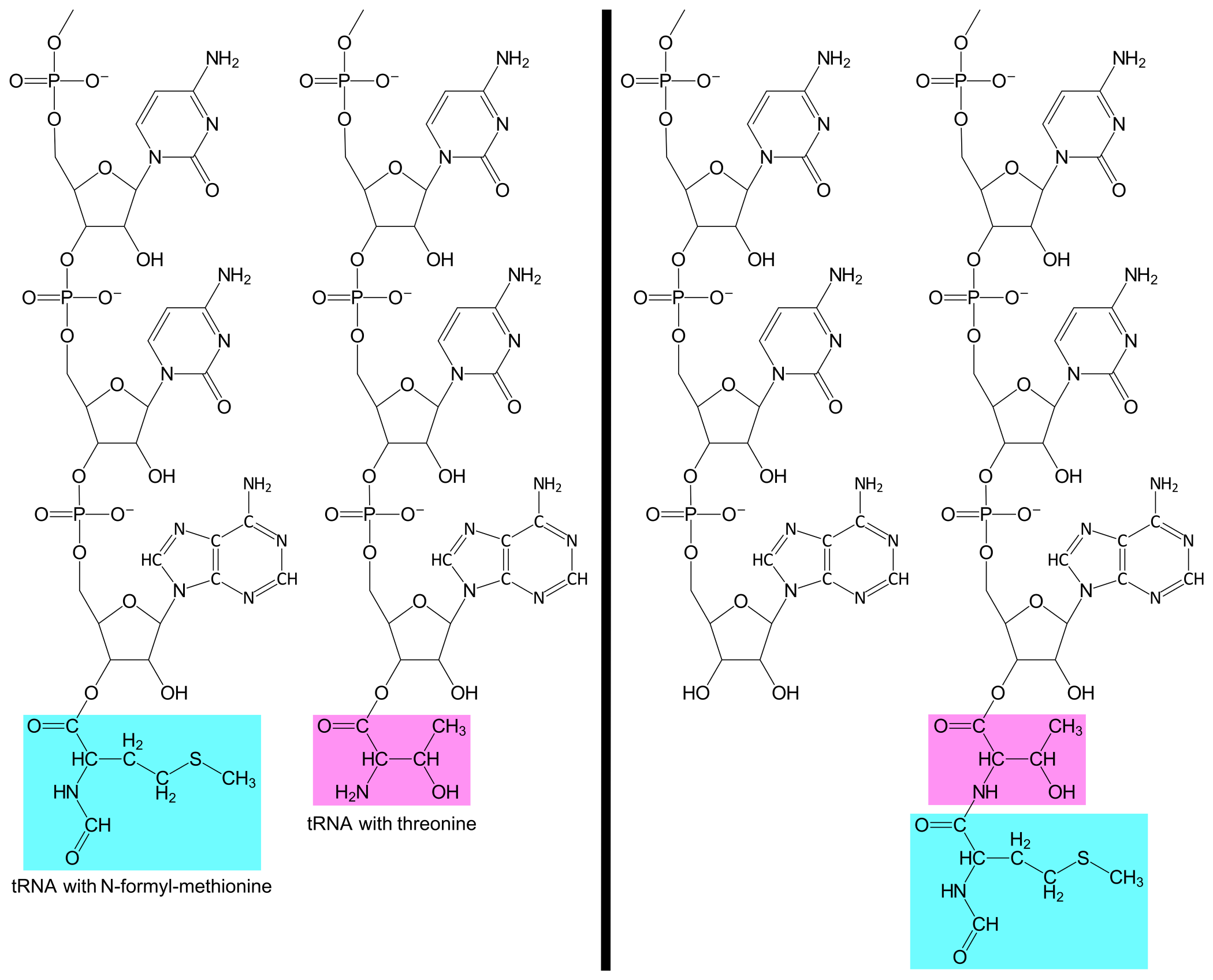

Translation is initiated with the binding of the ribosomal 30S subunit to the mRNA, at the 5'-end of the lacZ message. The 30S will then bind to a tRNAfMetUAC. This tRNA has the anticodon UAC and is bound to the amino acid N-formyl-methionin (abbreviated fMet). See the figure below. (Alternatively it is possible for translation to initiatie by the binding of the 30S first to the tRNAfMetUAC and second to the mRNA, the order of these two events don't matter.)

(Base sequences are conventionally written from the 5'-end towards the 3'-end, but in this article the anticodon-sequences will be written from the 3'-end towards the 5'-end because the anticodons has to be presented this way in the figures. All codon sequences in this article are written in the conventional manner, from the 5'-end towards the 3'-end.)

Thereafter the tRNAs UAC-anticodon binds to an AUG-codon in the mRNA, so that each of the three components in the complex (mRNA, tRNA, 30S subunit) are bound to the other two. The AUG codon functions as the lacZ message's start codon. Next, the ribosomal 50S subunit binds to the complex and creates a complete 70S ribosome that is ready to translate the lacZ message.

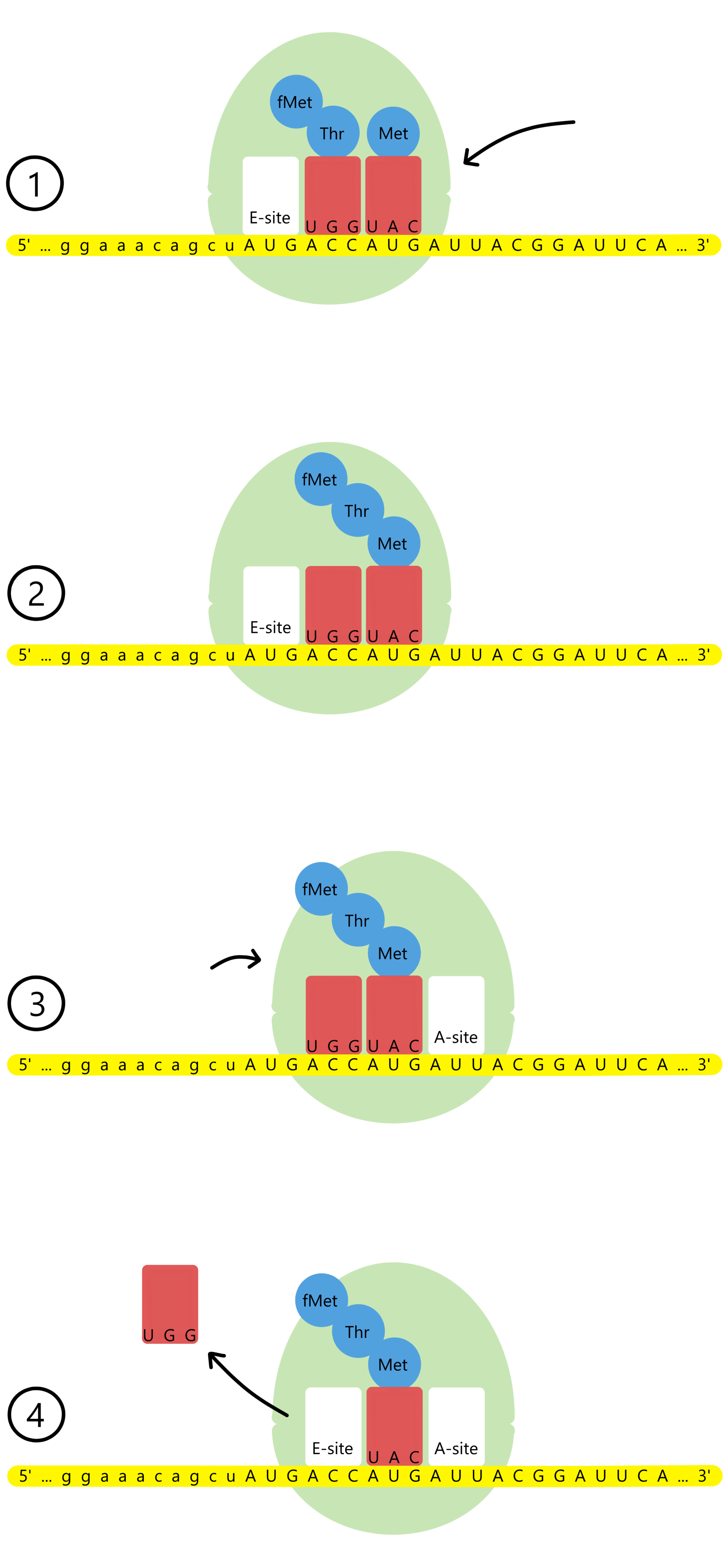

The ribosome has a track the mRNA can move through, and along the track there are three binding sites for tRNAs: the A-site, the P-site, and the E-site (A for aminoacyl, P for peptidyl, and E for exit). The P-site is currently occupied by tRNAfMetUAC base paired to the start codon AUG. The lacZ message's second codon, ACC, is exposed in the A-site.

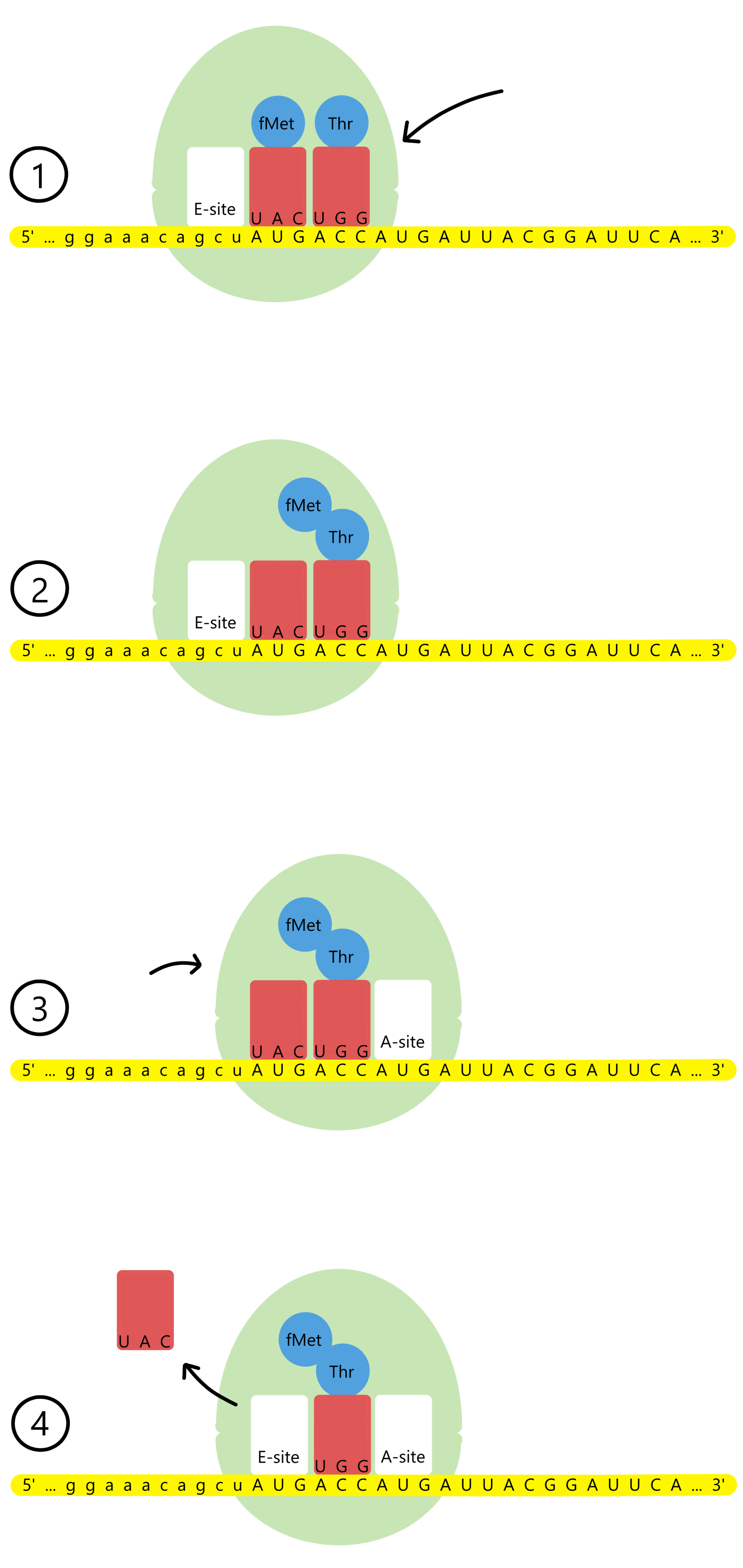

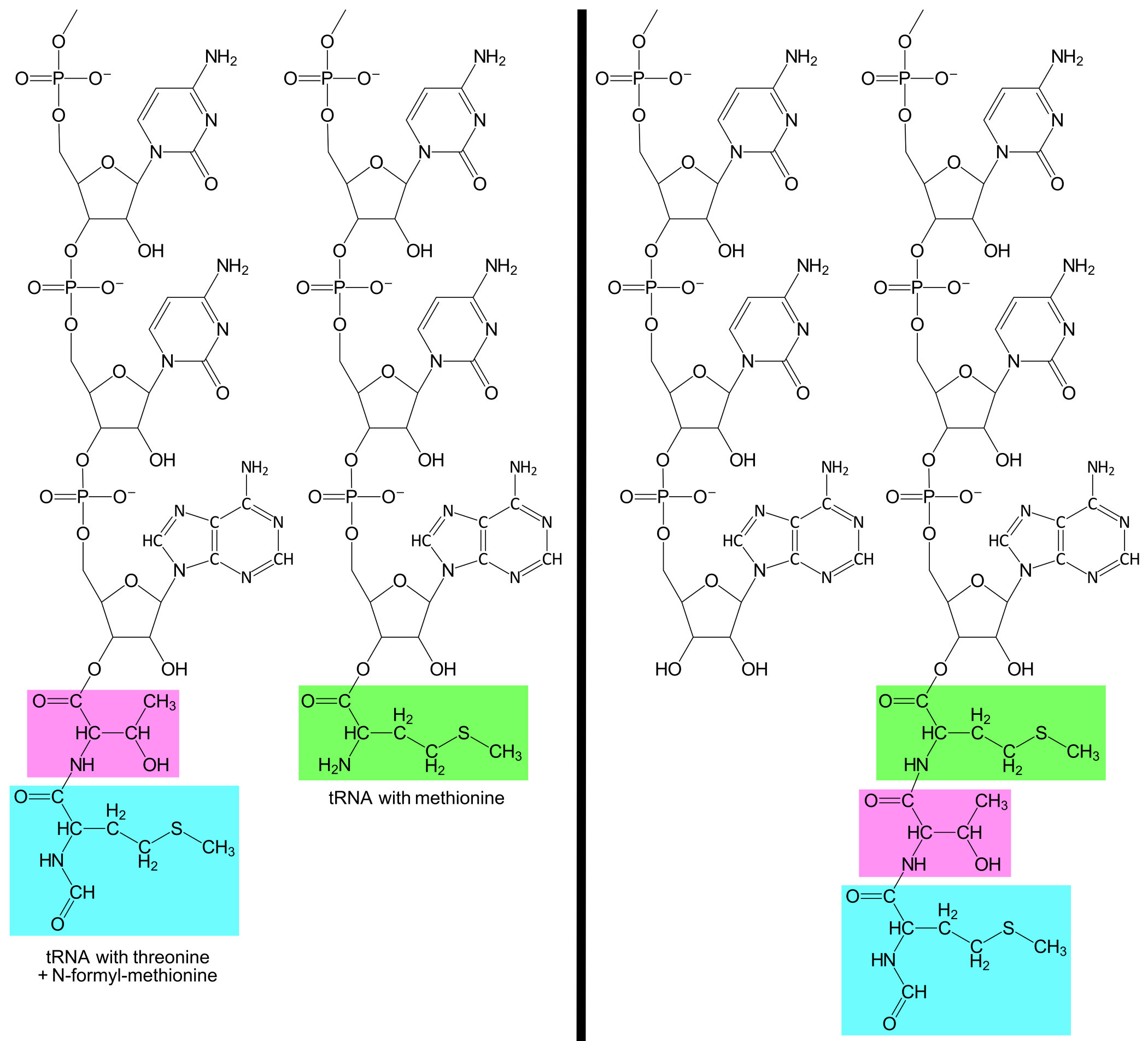

A tRNAThrUGG with the amino acid threonine (abbreviated Thr) enters the A-site and base pairs to the second codon. The ribosome can now catalyze the formation of a covalent bond between the amino acids fMet and Thr. At the same time, the covalent bond between fMet and tRNAfMetUAC is broken. The result is that tRNAThrUGG is now bound to a Thr, which is further bound to an fMet.

After the new bond is created, the ribosome moves a distance of three nucleotides along the mRNA, in the downstream direction (towards mRNA's 3'-end). This causes the start codon and tRNAfMetUAC to shift from the P-site to the E-site, while the second codon and tRNAThrUGG shifts from the A-site to the P-site, and the lacZ message's third codon, another AUG, is exposed in the A-site. tRNAfMetUAC is released from the E-site.

A tRNAMetUAC with methionine enters the A-site and base pairs to the third codon, AUG. The ribosome catalyses the formation of a covalent bond between Thr and Met. At the same time, the covalent bond between Thr and tRNAThrUGG is broken. The result is that the tRNAMetUAC now is bound to a Met, which is further bound to a Thr, which is further bound to an fMet.

The ribosome again moves a distance of three nucleotides downstream along the mRNA. This causes the second codon and tRNAThrUGG to shift from the P-site to the E-site, while the third codon and tRNAMetUAC is shifted from the A-site to the P-site, and the lacZ message's fourth codon, AUU, is exposed in the A-site. tRNAThrUGG is released from the E-site.

The translation continues with repeating cycles of binding of tRNA to the A-site, formation of a covalent bond between two amino acids, translocation of the ribosome along the mRNA, and release of tRNA from the E-site. For each cycle the amino acid chain grows one unit longer.

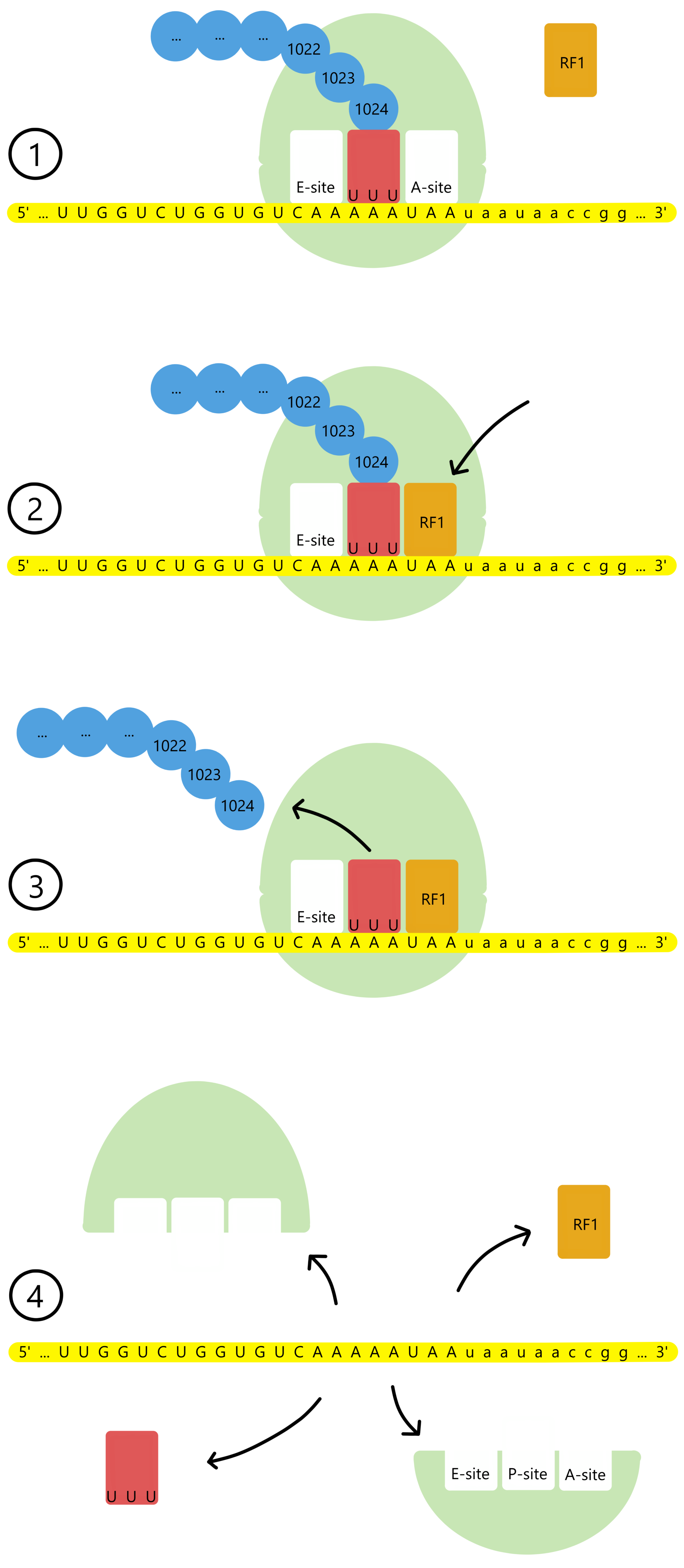

Eventually the amino acid chain grows to a length of 1024 amino acids and constitutes a complete LacZ protein (β-galactosidase). The lacZ message's last codon, UAA, becomes exposed in the A-site. UAA differs from all other codons in the lacZ message in that is does not base pair to a tRNA. Instead, a protein called Release Factor 1 (RF1) enters the A-site and binds to UAA.

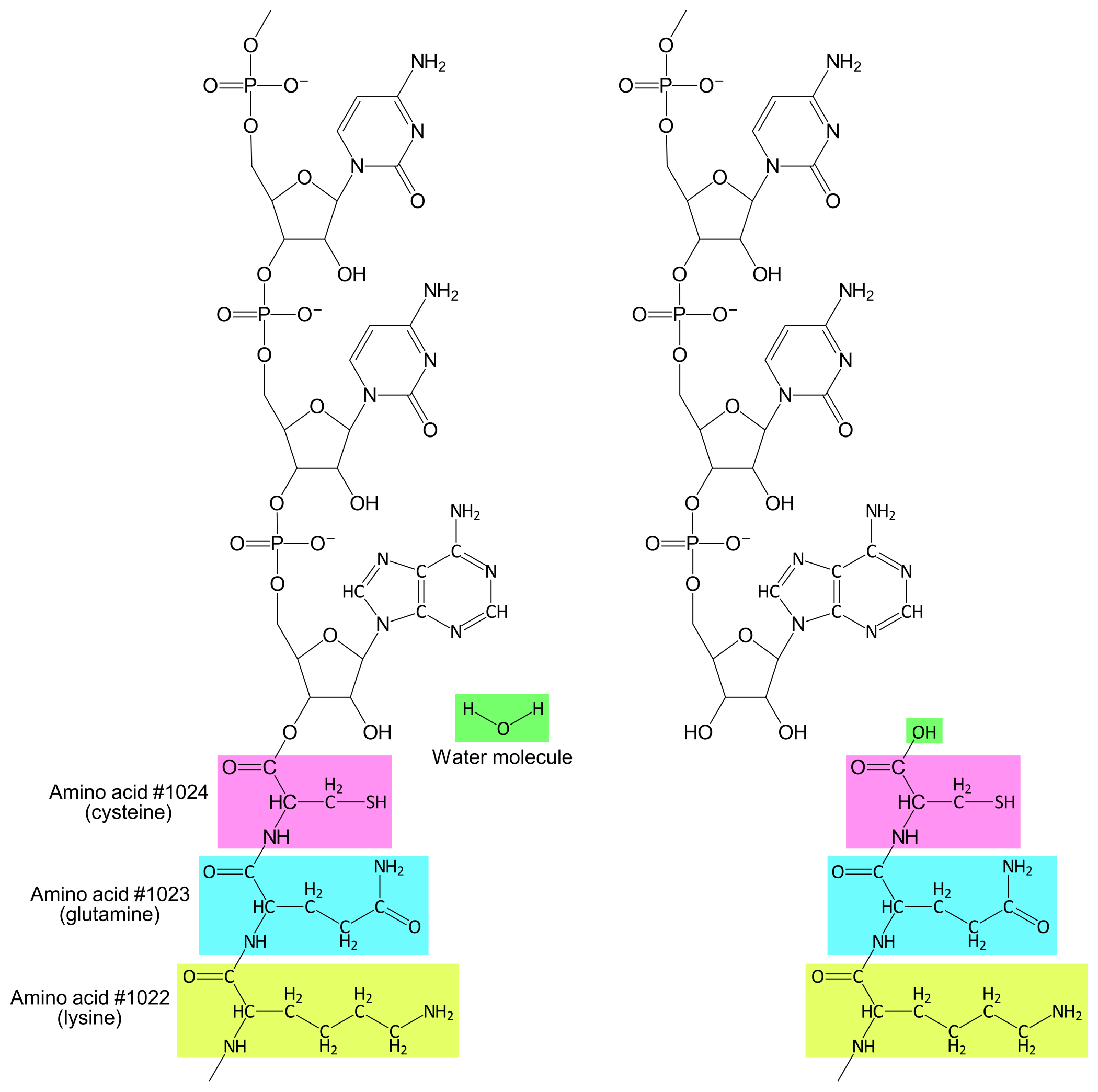

RF1 catalyzes the formation of a covalent bond between a water molecule and the 1024th amino acid. At the same time, the covalent bond between the 1024th amino acid and the tRNA is broken. This releases the LacZ protein from the tRNA and from the ribosome. Next, the ribosomal 30S- and 50S subunits and the mRNA, tRNA and RF1 all dissociate from each other, and the translation process is finished.

Translation in general

Based on the example of translation of the lacZ message, the general translation process can be described as follows:

A gene, and the protein message transcribed from the gene, consists of an array of base triplets called codons. A ribosome can bind to mRNA near the start of the protein message. The ribosome then translates the message's codons to amino acids one by one. First the start codon is translated, then the second codon, then the third codon, and so on. This requires that the ribosome moves towards the 3'-end of the mRNA during the translation process.

The translation is performed by aid of tRNAs bound to amino acids. The tRNA's anticodons base pairs with the codons of the message. For each pair of neighboring codons, the ribosome catalyzes the formation of a covalent bond between the two translated neighbor-amino acids. Initially the first and second amino acids are bonded together. Then the second and third amino acids are bonded together. Then the third and fourth amino acids are bonded together, and so on. This repeating process creates an amino acid chain.

The translation continues until the ribosome encounters the message's stop codon. A release factor binds to the stop codon and breaks the bond between the tRNA and the final amino acid of the chain. This releases the amino acid chain from the ribosome, ending the translation process.

On codons and anticodons

Since each codon contains three bases, and each base can be one of four different types (A, C, G, or U), there exist 4 × 4 × 4 = 64 different codons. Codon UAG can bind to Release Factor 1 (RF1), codon UGA can bind to RF2, and codon UAA can bind either RF1 or RF1. Both release factors have the same function: they release the amino acid chain from tRNA and terminate the translation process. The three codons UAG, UGA, and UAA are therefore called stop codons.

The remaining 61 codons are translated to amino acids. However, in E. coli there are not 61 different tRNAs/anticodons, there are only 41 different ones. Additionally, there are only 21 amino acids. Therefore, some codons have to bind the same tRNA/anticodon, and some tRNA must bind the same amino acid. For example, codons GCA and GCG both bind to tRNAAlaCGU, while codons GCC and GCU both bind to tRNAAlaCGG. That's four different codons binding two tRNAs which bind one amino acid, alanine.

| Codon | tRNA/RF | Codon | tRNA/RF |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAA | tRNALysUUU | CAA | tRNAGlnGUU |

| AAG | tRNALysUUU | CAG | tRNAGlnGUU, tRNAGlnGUC |

| AAC | tRNAAsnUUG | CAC | tRNAHisGUG |

| AAU | tRNAAsnUUG | CAU | tRNAHisGUG |

| ACA | tRNAThrUGU | CCA | tRNAProGGU |

| ACG | tRNAThrUGU, tRNAThrUGC | CCG | tRNAProGGU, tRNAProGGC |

| ACC | tRNAThrUGG | CCC | tRNAProGGG |

| ACU | tRNAThrUGG | CCU | tRNAProGGG |

| AGA | tRNAArgUCU | CGA | tRNAArgGCI |

| AGG | tRNAArgUCU, tRNAArgUCC | CGG | tRNAArgGCC |

| AGC | tRNASerUCG | CGC | tRNAArgGCI |

| AGU | tRNASerUCG | CGU | tRNAArgGCI |

| AUA | tRNAIleUAL | CUA | tRNALeuGAU |

| AUG | tRNAMetUAC | CUG | tRNALeuGAU, tRNALeuGAC |

| AUC | tRNAIleUAG | CUC | tRNALeuGAG |

| AUU | tRNAIleUAG | CUU | tRNALeuGAG |

| GAA | tRNAGluCUU | UAA | RF1, RF2 |

| GAG | tRNAGluCUU | UAG | RF1 |

| GAC | tRNAAspCUG | UAC | tRNATyrAUG |

| GAU | tRNAAspCUG | UAU | tRNATyrAUG |

| GCA | tRNAAlaCGU | UCA | tRNASerAGU |

| GCG | tRNAAlaCGU | UCG | tRNASerAGU, tRNASerAGC |

| GCC | tRNAAlaCGG | UCC | tRNASerAGG |

| GCU | tRNAAlaCGG | UCU | tRNASerAGG |

| GGA | tRNAGlyCCU | UGA | RF2 (tRNASecACU) |

| GGG | tRNAGlyCCU, tRNAGlyCCC | UGG | tRNATrpACC |

| GGC | tRNAGlyCCG | UGC | tRNACysACG |

| GGU | tRNAGlyCCG | UGU | tRNACysACG |

| GUA | tRNAValCAU | UUA | tRNALeuAAU |

| GUG | tRNAValCAU | UUG | tRNALeuAAU, tRNALeuAAC |

| GUC | tRNAValCAG | UUC | tRNAPheAAG |

| GUU | tRNAValCAG | UUU | tRNAPheAAG |

The fact that some anticodons bind two different codons is possible because the codon-anticodon-binding isn't based exclusively on AU- and CG-pairs. If the codon's third base (the base at the codon's 3'-end) is a G, then this G can base pair with either C or U in the anticodon. And if the codon's third base is a U, then this U can base pair with either an A or a G in the anticodon. In other words, the codon-anticodon-binding can involve a GU-pair, but this pair cannot involve the first or second codon bases, only the third codon base. An example of this is codon GGG, which can bind both tRNAGlyCCU and tRNAGlyCCC.

The binding between codon and anticodon will in some cases involve one of two unusual bases called inosine and lysidine (abbreviated I and L). In E. coli, inosine is found in tRNAArgGCI, where the anticodon GCI can bind the three codons CGA, CGC and CGU. Lysidine is found in tRNAIleUAL, where the anticodon UAL can bind the codon AUA.

(Stricktly speaking, inosine and lysidine are not the names of bases, they are the names of nucleosides. (A nucleoside is a base bound to a (deoxy)ribose, in contrast to the very similar word nucleotide, which refers to a base bound to a (deoxy)ribose bound to one or more phosphate groups.) The distinction between bases and nucleosides is not of importance here, so for simplicity's sake I will refer to inosine and lysidine as bases.)

Translation factors

The different phases of translation (assembly of the complete 70S ribosome on the mRNA, formation of covalent bonds between amino acids, and dissociation of the protein and the ribosome from mRNA) are referred to as initiation, elongation, and termination. In addition to the 30S- and 50S subunits, the mRNA and the tRNAs, the translation process also involves a number of proteins. These proteins are initiation factors 1, 2 and 3 (IF1, IF2, and IF3), elongation factors Tu, Ts, and G (EF-Tu, EF-Ts, and EF-G), release factors 1, 2 and 3 (RF1, RF2, and RF3), as well as the ribosome recycling factor (RRF). The functions of RF1 and RF2 has been described. The functions of the other translation factors will not be covered in this article.

Initiator-tRNA and start codons

In the example showing translation of the lacZ message, the start codon AUG binds to a tRNAfMetUAC. The third codon of the message, which also is an AUG, instead binds to a tRNAMetUAC. The former tRNA is called an initiator-tRNA while the latter tRNA is called an elongator-tRNA. Among all the 41 different anitcodons in E. coli, only the anticodon UAC is found both on an initiator-tRNA and on an elongator-tRNA. Each of the remaining 40 anticodons are only found on an elongator-tRNA. E. coli therefore has 41 different elongator-tRNAs and one single initiator-tRNA, that being initiator-tRNAfMetUAC.

The initiator-tRNA is the only tRNA that can bind to the ribosomal P-site in the 30S subunit before the 30S- and 50S subunits are assembled into a complete 70S ribosome. This means that translation always begins with an initiator-tRNAfMetUAC, independent of which protein-message is being translated. However, the initiator-tRNA cannot bind to the ribosomal A-site in the 70S ribosome, only the elongator-tRNAs can do this. This difference in binding is caused by differences in molecular structures.

(fMet is a modified methionine where the nitrogen atom of the amine group is covalently bound to a formyl group, hence the name N-formyl-methionine. I don't know enough about the formyl-modification to comment on its function. In eukaryotic organsims, the initiator-tRNA carries a regular methionine rather than an N-formyl-methionine, so that the initiator-tRNAMetUAC and the elongator-tRNAMetUAC both carry the same amino acid.)

If translation always begins with an initiator-tRNAfMetUAC, does this mean that all genes in E. coli starts with an AUG codon? No, actually not. In some genes the codons GUG, UUG, or AUU is used as a start codon. Regardless of which base triplet that functions as the start codon, it is always initiator-tRNAfMetUAC that binds to the start codon.

(I'm not entirely certain, but in the cases of GUG and UUG acting as start codons I think the first base of the codon does not base pair to the anticodon of the initiator-tRNA. And in the case of AUU I think the third base of the codon does not base pair to the anticodon. That is, I don't think there can be GU- or UU-pairs involving the first base of the codon, nor UU-pairs involving the third base of the codon. Instead I think that the initiator-tRNAfMetUAC binds to the alternative start codons with only two base pairs, which are regular AU- and CG-pairs.)

(When the entire E. coli DNA had been sequenced, a total of 4288 protein-coding genes were identified (Blattner 1997). These 4288 included proven genes as well as predicted genes (DNA-sequences that are believed to be genes). Of the 4288 genes there were 3542 (83%) that started with AUG, 612 (14%) that started with GUG, and 130 (3%) that started with UUG. Later, two genes starting with AUU were identified in E. coli (Binns 2002). In the BioCyc database for E. coli, last updated in 2023, there are listed 4312 protein-coding genes. It is therefore possible that Blattner's start codon frequencies are quite accurate, assuming that most of Blattner's predicted genes were real genes and assuming that Blattner generally identified the correct start codons of those genes.)

tRNASecACU and the selenocysteine insertion sequence

UGA triplets usually function as stop codons, but will in some cases function as selenocysteine codons. If an UGA is meant to be translated to selenocysteine the UGA will be followed downstream by a selenocysteine insertion sequence (SECIS). tRNASecACU first binds to the protein SelB, and thereafter SelB binds to the SECIS. This holds tRNASecACU in position near the UGA codon. When a ribosome approaches and the UGA codon enters the ribosome's A-site, the tRNASecACU is ready to be inserted into the A-site (see Figure 9 in Heider 1992).

If tRNASecACU doesn't bind to the A-site in this manner, an RF2 protein will instead enter the A-site and cause termination of translation. (Additional details about SECIS are presented in a separate article.)

The Shine-Dalgarno sequence

In E. coli, the majority of the protein messages contain a so-called Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD sequence) a short distance upstream of the start codon. The ribosomal 30S subunit consists of different ribosomal proteins and a 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and the SD sequence can base pair to a complementary sequence in the 3'-end of the 16S rRNA. For example, seven bases upstream of the lacZ message's start codon there is an AGGA sequence, which can base pair to UCCU in the 3'-end of 16S rRNA:

||||

16S rRNA: 3'OH-AUUCCUCCACUAG-5’

Translation of a protein message is initiated by the binding of an mRNA and an initiator-tRNA to the ribosomal 30S subunit. Next, the start codon of the mRNA and the anticodon of the initiator-tRNA has to base pair together. The function of the SD sequence is to aid in the positioning of the start codon in the ribosomal P-site, where the initiator-tRNA is bound, so that the start codon and anticodon more efficiently can bind together. (Additional details about the SD sequence are presented in a separate article.)

How the translational start site is selected

(For those who are not familiar with the concept of free energy this section will be more difficult than the other sections in this article.)

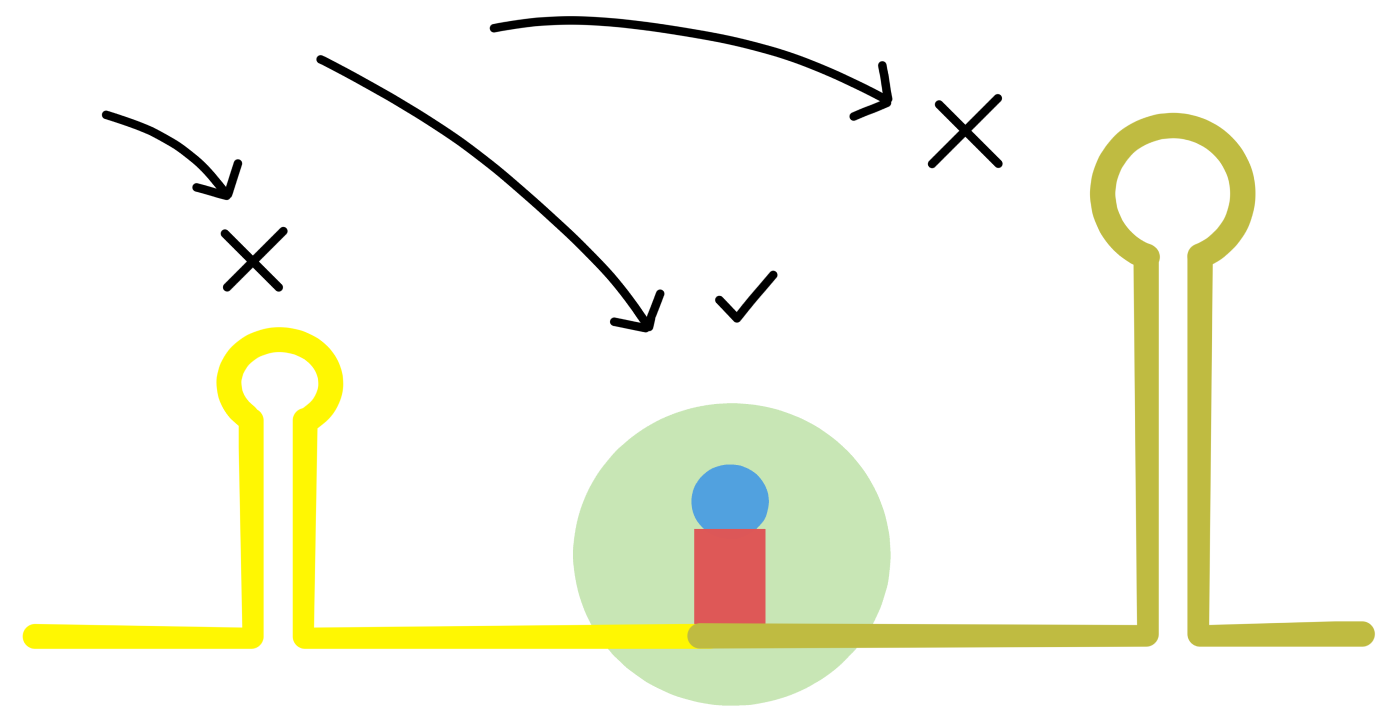

Translation begins with the ribosomal 30S subunit binding to the start of a protein message, and a start codon (usually AUG) base pairs to an initiator-tRNA. How can the 30S subunit distinguish the start of a protein message from other locations in the mRNA?

The start codon itself, whether it is AUG or something else, cannot signal the ribosome where to bind. A lot of AUG codons do not function as start codons, as can be readily seen in the base sequences of the three lactose genes. (All AUG triplets that aren't split between two lines can be highlighted by searching with ctrl+f "ATG", where ATG has to be used in place of AUG because the link shows the DNA sequence, not the mRNA sequence. Just as an example for anyone who don't care to do this themselves, the search yields 56 AUG triplets spread throughout the lacZ sequence.)

For a long time it was thought that the Shine-Dalgarno sequence was involved in start site selection. However, according to Saito 2020, 30S subunits containing mutated 16S rRNA could still bind to the correct start of protein messages, even thought the mutated 16S rRNA could not base pair to the SD sequences of these messages. The SD sequence can therefore not be involved in the ribosome's ability to initiate translation only at the correct start sites.

Something that may be of significance is intramolecular base pairing in the mRNA. As mentioned earlier, two complementary sequences in the same RNA can base pair together to form a "stem". The two sequences of the stem are connected by a loop-sequence. En example of a stem-loop in an mRNA is shown in Figure 1 in de Smit 1990. (de Smit refers to stem-loops by the alternative name "hairpin".)

A stem is not a permanent structure: the two base paired sequences can break apart and become "unfolded". Unfolded complementary sequences can later base pair together again, restoring the stem-loop structure. When a cell contains many mRNAs, some of the complementary sequences will form stem-loops while some will be unfolded.

The proportion of the complementary sequences which at any point in time form stem-loops is related to the structural stability of the stem-loop. Stability is quantified by the "change in free energy" that occur when the unfolded sequences base pair together into a stem-loop. Change in free energy is symbolized with ΔG, where lower (more negative) values of ΔG indicate more stable stem-loops.

de Smit introduced a series of mutations in a stem-loop containing the start codon of a protein message (see de Smit's Figure 2). Some of the mutations were expected to reduce the stability of the stem-loop, whereas other mutations were expected to increase the stability (see de Smit's Table 1). A good correlation was found between increased stem-loop stability and decreased translation of the protein message (that is, a good correlation between ΔG and "relative expression", see de Smit's Table 1 and Figure 4B). In the mutant with the most stable stem-loop, translation of the protein message was reduced practically to zero (see mutant 14 in Table 1).

A possible explanation for the correlation between stem-loop stability and translation of the message is that ribosomes can only bind to the start of a message when that part of the mRNA is unfolded. Higher stability of the stem-loop means that fewer start sites will be available in unfolded form, reducing the ribosome's ability to bind and thur reducing translation.

If this is true, then it is possible that stem-loop stability can be used to distinguish message start sites from other parts of mRNA: the sequences of start sites may only be able to form stem-loops of low stability, while other parts of the mRNA may be able to form more stable stem-loops. Computer-based analyses of protein messages in E. coli have indicated that this is indeed the case (see Tuller 2010 and Gu 2010, Tuller refers to intramolecular base pairing in mRNA as "folding" while Gu uses the term "secondary structure"). It therefore appears that stem-loops is one of the factors that influences the ribosome's ability to select the correct start sites.

(One can ask: if base paired sequences in mRNA can prevent the ribosome from binding the mRNA outside of the message start sites, can they not also prevent the ribosome from moving along the mRNA during the elongation phase of translation? The answer is that when the ribosome moves along the mRNA it has the ability to unfold any base paired sequences ahead of itself (Takyar 2005). This ability is called helicase activity. It is still possible that the presence of stable stem-loops in the ribosome's path reduces the translation speed of the ribosome, this I do not know.)

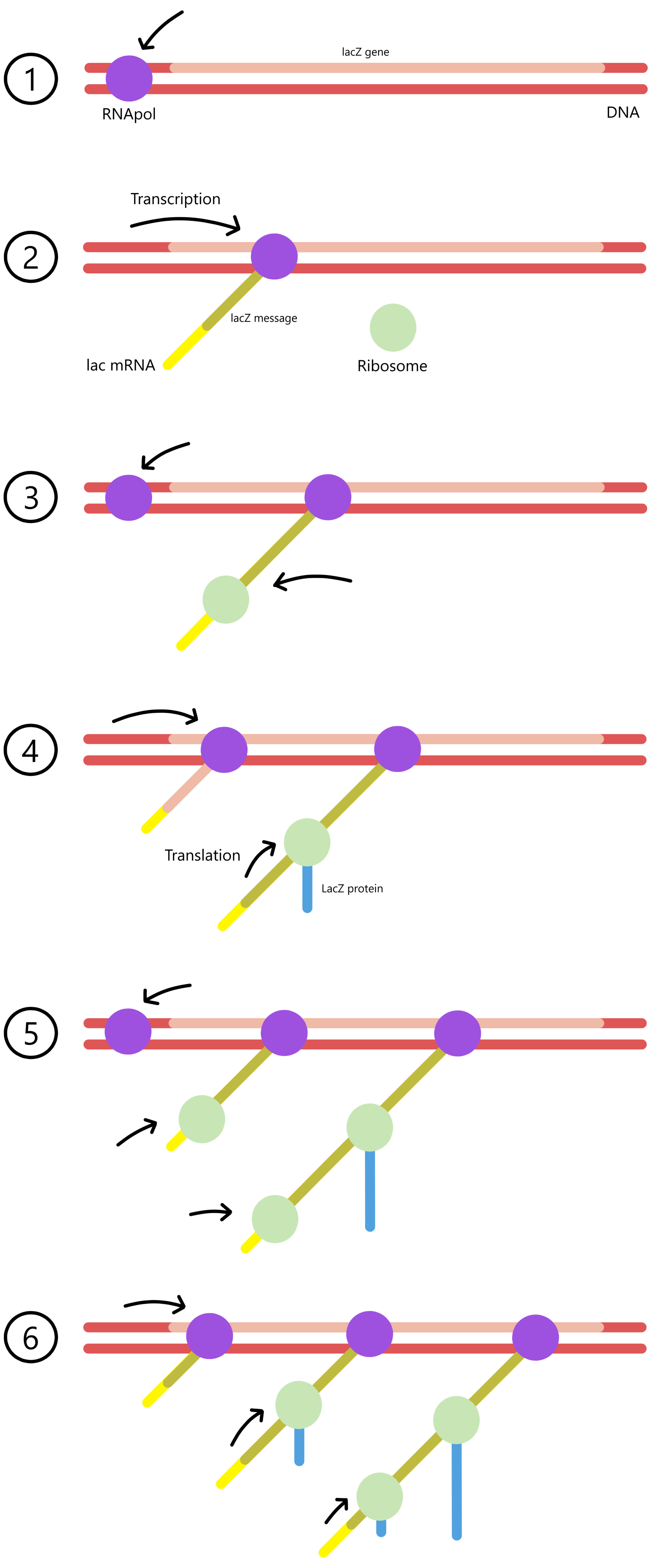

Simultaneous transcription and translation

During transcription, the mRNA is built from its 5'-end towards its 3'-end, and during translation the ribosome moves towards the mRNA's 3'-end. In bacteria it is therefore possible for translation of a message to begin while the mRNA carrying the message is still being transcribed. In fact, a ribosome can bind to an RNA polymerase before transcription begins. The ribosome can then begin translation as soon as the 5'-end of the mRNA has been produced. (Simultaneous transcription and translation of mRNA cannot take place in eukaryotic organisms, because transcription and translation in eukaryotes are physically separated by the nuclear membrane.)

After a ribosome has bound to the start of a protein message and begun to elongate, a second ribosome can bind to the same message and begin to elongate before the first ribosome has completed the translation. A message can therefore be translated by multiple ribosomes at the same time, in the same way that a gene can be transcribed by multiple RNApols at the same time.

See simultaneous transcription and translation in E. coli (click on Figure 1 in the link to open the image). The two thin lines that cross through the image diagonally are DNA. The arrow in the upper left corner points at what assumably is a RNApol bound to the promoter of an undetermined gene. The black chains attached to the DNA are mRNA with attached ribosomes. In this image the DNA is transcribed from the left towards the right, so that the mRNAs are shorter in the left side of the image, and longer in the right side. Proteins are not visible (I don't know why not). A short mRNA in the right part of the image is possibly the product of a longer mRNA that happens to have been cut in two pieces.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases

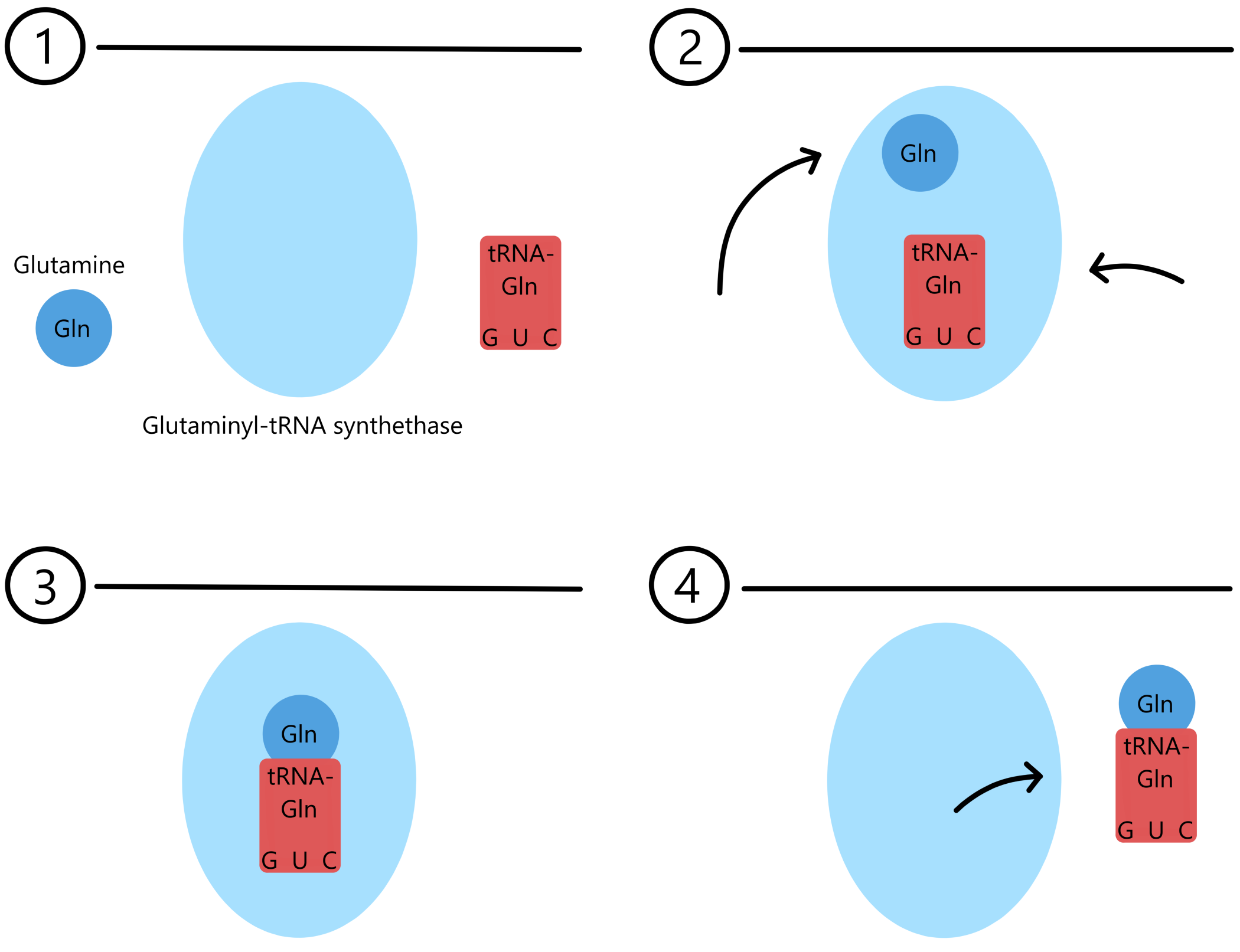

As mentioned, there are 21 different amino acids and 41 different tRNA/anticodons. To bind each amino acid to the correct tRNA(s) the cell deploys a collection of enzymes called Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARS). Most cells, including E. coli, have twenty different AARS that each can bind one amino acid (there is no AARS for selenocysteine). Each AARS can also bind to one or a few of the different tRNAs. An AARS distinguishes amino acids from each other based on their variable groups. tRNAs are distinguished from each other based on differences in base sequence and molecular structure.

Once an AARS has bound both an amino acid and a tRNA, the AARS can catalyze the formation of a covalent bond between the tRNA's 3'-hydroxyl and the amino acid's carboxylic acid, thus creating an aminoacyl-tRNA (see Figure 1).

For example, Glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase (GlnRS) is an AARS that binds to the amino acid glutamine, and to one of two tRNAs: either tRNAGlnGUC or tRNAGlnGUU. When GlnRS binds glutamine and the former tRNA, the product will be a Glutaminyl-tRNAGlnGUC. When GlnRS binds glutamine and the latter tRNA, the product will be a Glutaminyl-tRNAGlnGUU.

A tRNA bound to an amino acid is said to be "charged", while a tRNA that is not bound to any amino acid is said to be "uncharged".

In organisms that use selenocystin (sec), the formation of Selenocysteinyl-tRNASecACU is dependent on the two enzymes Seryl-tRNA synthetase (SerRS) and Selenocysteine synthetase. First, the SerRS binds serine to tRNASecACU, creating a Seryl-tRNASecACU, and then Selenocysteine synthethase modifies the Seryl-tRNASecACU to a Selenocysteinyl-tRNASecACU.

("Sec" in tRNASecACU therefore means that the function of this tRNA is to translate a codon to selenocysteine, it does not mean that this tRNA always is bound to selenocysteine.)

On the names "messenger-RNA" and "transfer-RNA"

In eukaryotes the processes of transcription and translation are physically separated by the nuclear membrane. Genes are transcribed to mRNA in the nucleus, the mRNA moves through the nuclear membrane and out into the cytosol where the ribosomes are located, and the ribosomes translate the mRNA to proteins. The name "messenger-RNA" is therefore fitting in eukaryotes. In bacteria, on the other hand, transcription and translation are performed at the same time and place, so the name "messenger-RNA" doesn't really make much sense in bacteria. Despite of this, the name messenger-RNA is used in both eukaryotes and bacteria.

The name transfer-RNA has its origin in a text from 1958, where it was written that “it was shown that the RNA of a particular fraction of the cytoplasm hitherto uncharacterized became labeled with C14-amino acids in the presence of ATP and the amino acid-activating enzymes, and that this labeled RNA subsequently was able to transfer the amino acid to microsomal protein in the presence of GTP and a nucleoside triphosphate-generating system.” (Hoagland 1958) (Now that the translation process is better understood, I think the name "translator-RNA" would have been more fitting.)

Summary

Translation of a base sequence to an amino acid sequence involves base triplets called codons in mRNA and anticodons in tRNA. The translation process is controlled by a ribosome, a large molecular structure composed of different ribosomal proteins and ribosomal RNAs. The ribosome catalyzes the formation of the covalent bonds that bind the amino acids together into a chain.

In addition to mRNA, tRNA, and a ribosome, the translation process is also dependent on a set of proteins called initiation factors, elongation factors, release factors, and the ribosome recycle factor. Translation also depends on a set of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases that "charge" the tRNAs with amino acids.

In E. coli there is one single initiator-tRNA, called tRNAfMetUAC, as well as 41 different elongator-tRNAs (with 41 different anticodons). The base in the third position of a codon can form GU-pairs with a base in an anticodon, which makes it possible for the 41 different tRNAs/anticodons to bind 62 different codons. Two of the elongator-tRNAs have anticodons containing unusual bases: one anticodon contains the base inosine, while another anticodon contains lysidine.

UGA triplets usually act as stop codons, but will in some cases act as selenocysteine codons. In the latter case the UGA has to be followed downstream by a SECIS (selenocysteine insertion sequence).

Intramolecular base pairing with high stability can prevent a ribosome from binding to mRNA. One of the factors that distinguish correct message start sites from other parts of mRNA is that the correct start sites generally don't form stem-loops of high stability, and therefore tends to be available in unfolded form.

A gene can be transcribed by multiple RNA polymerases simultaneously, and a message in mRNA can be translated by multiple ribosomes at the same time as RNApol transcribe this mRNA.

References

Binns, Masters

(2002): Expression of the Escherichia coli pcnB gene is translationally limited using an inefficient start codon: a second chromosomal example of translation initiated at AUU. Free article

Blattner, Ill, Block, Perna, Burland, Riley, Collado-Vides, Glasner, Rode, Mayhew, Gregor, Davis, Kirkpatrick, Goeden, Rose, Mau, Shao

(1997): The Complete Genome Sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Paid article

Gu, Zhou, Wilke

(2010): A Universal Trend of Reduced mRNA Stability near the Translation-Initiation Site in Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes. Free article

Hoagland, Stephenson, Scott, Hecht, Zamecnik

(1958): A soluble ribonucleic acid intermediate in protein synthesis. Free article

Komine, Adachi, Inokuchi, Ozeki

(1990): Genomic Organization and Physical Mapping of the Transfer RNA Genes in Escherichia coli K12. Paid article

Saito, Green, Buskirk

(2020): Translational initiation in E. coli occurs at the correct sites genome-wide in the absence of mRNA-rRNA base-pairing. Free article

de Smit, van Duin

(1990): Secondary structure of the ribosome binding site determines translational efficiency: A quantitative analysis. Free article

Takyar, Hickerson, Noller

(2005): mRNA Helicase Activity of the Ribosome. Free article

Tuller, Waldman, Kupiec, Ruppin

(2010): Translation efficiency is determined by both codon bias and folding energy. Free article